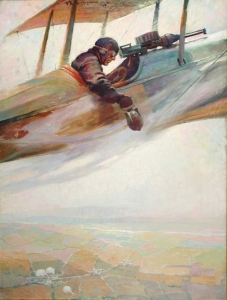

Frank E. Schoonover (1877-1972)|Getting Ready to Go Up (Contact), 1918|Illustration for “Our War Eagles” in Red Cross Magazine (July 1918): 17;Contact was also used as paper book cover image for Deeds of Heroism and Bravery, ed. by Elwyn A. Barron (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Pubs., 1920)|oil on canvas|Collection of Don and Martha DeWees

Frank E. Schoonover (1877-1972)|Dropping Bombs Over German Country (Bombing), 1918|Illustrations for “Our War Eagles” in Red Cross Magazine (July 1918): 18|oil on canvas|Collection of Don and Martha DeWees

Contact and Bombing were painted by Frank E. Schoonover as part of a series of four illustrations focused on the activities of American aviators and their ground crews published in the Red Cross Magazine during World War One (also known as The Great War and The War to End All Wars.) Despite years of isolationism, American troops arrived in France to join the allied forces in the beginning of July 1917. The war ended in November of 1918. The purpose of the Red Cross Magazine story and images, in part, was to focus America’s attention on their boys overseas. Because the illustrations were created for the American Red Cross, the story was no doubt also used as a prod to help raise monies to be used to assist American troops involved in the war effort.

Prior to America’s entry into The Great War, the American Red Cross was focused on first aid, water safety, and public health programs. With the onset of the war, the Red Cross experienced explosive growth: the number of local chapters grew from 107 in 1914 to 3,864 in 1918; individual membership expanded from 17,000 to more than 20 million adult and 11 million Junior Red Cross members. Overseas the Red Cross staffed hospitals and ambulance companies and recruited 20,000 registered nurses to serve the military.

The article these images accompanied was titled, “Our War Eagles.” Interestingly the designation of “war eagles” was later used to identify the war airplanes and their staff of World War II through the Korean War era.* Prior to the Great War the United States military air contingent was the Aeronautical Division of the U. S. Signal Corps. In 1914 their designation changed to the Aviation Section of the U. S. Signal Corps. For a brief period in May 1918 they were known as the Division of Military Aeronautics and then they were transformed into the U. S. Army Air Service.**

Aircraft began to be used militarily for reconnaissance as early as 1911 in the Italo-Turkish War. Soon aviators were dropping grenades and taking aerial photography. By 1914, planes and manned observation balloons were used for reconnaissance and for ground attacks. The two-seater plane in Contact appears to have been modeled after a Curtiss JN4 and a JN-4D, known as a “Jenny.” It was never used in combat, but served to train pilots of the U. S. Air Service. The plane’s wing insignia, a white five-pointed star with a red central circle inscribed in a blue circle, was carried on the uppermost and lowermost surfaces of the wings, as seen in Contact, and was used as the national marking of U. S. airplanes from May 19, 1917 through January 11, 1918. The plane’s rudders were painted with a blue-white-red striping and the plane’s fuselage carried no markings.

In his painting Bombing, Schoonover may have fudged the technical reality of the air plane’s wings (which is not a Jenny, but probably a sleek French design) and their bracing, in order to provide a clearer view of the pilot and the bomb. Mounted in front of the pilot, who holds a bomb in his right hand, is a machine gun. According to a report produced after the war was over, one of the greatest challenges was creating an internal timing device that would synchronize the triggering of the machine gun with the movement of the propeller out of harms way.*** As we can see in Contact, another solution was to cover the propeller’s blades with metal armor in an attempt to protect the wooden blades. The pastel palette Schoonover used in these paintings belies the seriousness of the aviator’s actions. In Bombing, notice how Schoonover painted the wisps of cloud slipping over the wing to signify the motion of the machine through the air. These paintings are almost lyrical depictions of a horrific reality.

*War Eagle is also the battle cry and symbol of Auburn University; and in the 19th century the war eagle as used as the rank insignia of a United States Colonel.

** They did not become the Air Corps until July of 1925.

*** “Aircraft Machine Guns” from “United States Army Aircraft Production Facts,” compiled at the request of the Assistant Secretary of War by Col. G. W. Mixter, A. S., A. P. and Lieut. H. H. Emmons, U. S. N. R. F., Of the Bureau of Aircraft Production (January 1919), see https://www.theaerodrome.com/forum/aircraft-articles/31798-aircraft-machine-guns.html The synchronization gear was invented by a Dutch person in Germany n 1915.

February 25, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum