Everyman, Meet Somebody: Characterization and Melodrama in Rockwell’s Four Freedoms

Despite pretensions to eternity, we know that art is fixed in time, rooted to the moment of its creation and distribution. The historical exigencies that led to the creation of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms suite are well known. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had designated the Freedoms—freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—in his January 1941 Message to Congress. In May 1942, when Rockwell toured the US Department of War, casting about for opportunities to be helpful, the memory of Pearl Harbor was still fresh, and recent news from the Pacific theater of war had been mixed. Seventy-six thousand American and Filipino troops had surrendered to Japanese forces on the Bataan Peninsula, Philippines, on April 9. The US Army Air Forces’ Doolittle Raid on Tokyo (emotionally satisfying, if not particularly effective) had followed on April 18. All that spring, from Hawaii to California to Washington State, government agents were rounding up Japanese Americans, stripping them of their property, and depositing them in isolated camps. When Rockwell finished the suite at the end of 1942, the tide had turned in the Pacific, although a bloody slog remained. Europe remained occupied by the Axis powers; Americans had yet to land in Sicily, and the Allied invasion of Normandy was still eighteen months off. All told, the Four Freedoms paintings were undertaken in a deeply unsettled moment.

Our return to Rockwell is likewise grounded in time. Revivals always reveal latter-day concerns. Amid the tumult of 2016–18 in the United States, we should note that until quite recently, any attempt to reengage with Rockwell’s Four Freedoms might have come off as quaint or triumphalist. After all, the victory over fascism and the achievements of the postwar era have been amply celebrated. Paeans to the so-called greatest generation had grown cliché within the first full decade of this new century. The enterprise this catalog marks might well have been a giant bore. But alas, no. Today we take up the Four Freedoms newly alert to the dangers of complacency. We face radical discontent of more than one stripe and eroding trust in our institutions, even in the very legitimacy of our elections.

All of this matters greatly. Our civic health is subject to other measurements, too. The plague of cheap talk and bad faith in contemporary America threatens our thinking. The headlong rush to the battlements to fend off Vandals, whoever they may be, erodes our capacity to weigh carefully and judge discerningly. Discernment takes practice. And culture provides the raw material to practice on, valuable precisely because life and limb are not at stake. If we have grown used to the notion of culture war, that is an indictment of our era.

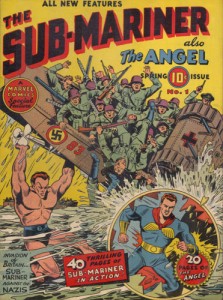

In divided times, a reliance on melodrama can be a safe—if also culturally stunting—path. Certainly the fare at the movies has descended into juvenilia, particularly comic book melodrama. Ironically, the superheroes who nowadays stalk the multiplex were invented by Jewish kids in the late 1930s. They were understandably in thrall to the wish fulfillment of special powers, having learned through family networks of the mortal danger to European Jewry. Well before the United States entered the war for which Rockwell propagandized, superheroes had begun battling Nazis. As for today, we might do with fewer cosmic battles against galactic villains. Our requirements are simpler: legislators, holiday partygoers, everyday persons who object to indecency. But because big-dollar returns for The Avengers and its ilk are predictable, the studios continue to serve up spectacular, repetitive fare.

Fig. 1. Alex Schomburg (1905–1998). Cover illustration, The Sub-Mariner No. 1, “Deep-Sea Blitzkrieg,” Timely Publications, Spring 1941.

By such a route—a reflection on melodrama—do I arrive at what may seem like an impertinent question. As we return our thoughts and gaze to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s alliterative quartet and Norman Rockwell’s visualizations of it, we have an obligation to ask: Are these things any good? That is, are the illustrated Four Freedoms cultural work of high merit? Or should they, all these decades later on, be best understood primarily as skillfully wrought pablum?

That latter formulation might induce a form of mid-twentieth-century post-traumatic stress disorder in Rockwellians. Not again! Shouldn’t the steady rehabilitation of Norman Rockwell’s reputation among (some) critics and (certain deep-pocketed) collectors have set such loaded questions to rest? In many respects, yes. Rockwell’s visual range, gift for staging, command of his medium, productivity, and durability with audiences establish him as a major figure in twentieth-century American visual culture. And yes, the prior terms of his exclusion from the master narrative of American art history remain mostly in force and owe much to high cultural disdain for the products of consumer culture.[i]

But that is no matter. Historically and critically speaking, Rockwell matters now, just as previously scorned categories of cultural production like genre fiction and television do. The old hierarchies of taste have aged poorly, and we can be thankful for that.

But that is not the whole story. To dispense with the vertical axis of high and low is not to abandon judgment or forswear criticism. To the contrary, a vital pluralism relies on rigor, lest it slip into naive enthusiasm or louche fellow-traveling. Let’s take Rockwell seriously. What has he got to show us?

On Method

As a practical matter, Rockwell’s pictorial enfleshment of Roosevelt’s theorized transnational rights succeeded and wildly so. Audiences identified with the pictures because they recognized themselves in them. That may sound like an utter commonplace but should not be taken as such. Reverse engineer the pictures: the freedoms themselves are quite abstract. How and by whom should images depicting them be populated? Ponder the creative knot that sits at the intersection of modern personhood, shifting modes of representation, and the machinery of mass culture. Who is Everyman? (Note: I use “man” advisedly.)

Artists and writers had been working on this problem since the turn of the century. The notion of Modern Man was still fresh in the early 1940s. Speaking broadly, he was imagined to have transcended class and escaped (or realized) history by one of several routes at a fork in the ideological road paved two decades earlier: via abstraction to the left, via advertising to the Calvin Coolidge right, or via the Volk to the fascist right.[ii] After Pearl Harbor, only the first two were viable in the United States. Both routes required generalization, the first through social realism inflected by abstraction (itself driven by analytical reduction of early social scientism), and the second through alternately arcadian and urbane fantasies of consumerist self-realization. Depression-era American visual culture featured human representations of both kinds: the noble laborers of Works Progress Administration (WPA) posters and murals and the dreamy stock guys and gals of print advertising. (Notably, almost all such heroic generalizing in mainstream print involved white people. When other racial groups were generalized, mockery prevailed.)

Fig. 2. Maurice Merlin (1909–1947). Mobilizing Michigan for Farm and Factory, 1941–43. Poster, Michigan Art and Craft Project, Work Projects Administration. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Fig. 3. George Petty (1894–1975). “’Snowonder she likes Old Golds!” Two-color print advertisement, Collier’s, January 28, 1939.

These were the vocabularies available to an American illustrator who aspired, as Rockwell did, to give plastic form to universalizing language aimed at a wartime popular audience. The abstractionist forswore anecdote, simplifying planes and eliminating local detail to create a sense of the mythic. Rockwell did the opposite: he committed to particulars. His Everyman would be Somebody.

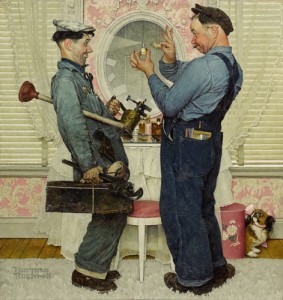

As a matter of general practice Norman Rockwell cast the characters in his paintings much as a film director might, painstakingly building his tableaux through repeated sittings and photo shoots. All of his characters were somebodies. The method suggests the illustrator as a documentary allegorist, which is accurate as far as it goes. But Rockwell’s persuasiveness as a maker of illusions—skillfully rendering characters as well as objects and settings—served as a Trojan horse. The illustrator’s verisimilitude masked the hidden caricaturist within, the secret to his beloved warmth and liveliness. As a comparison of his photographic contact sheets and his finished paintings suggests, Rockwell exaggerated unmistakably, investing—goosing, really—a given pose or a model’s expression with a boost of animation at a controlled rate; the exaggeration was perceptible, if barely. Cloaked in realist garb, such comedic adjustments went unseen. The maneuver is most evident in Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers, and is easiest to spot in particularly performative scenes, such as The Gossips (1948) and Two Plumbers (1951), the latter reproduced with but one of the forty-five reference photographs shot for the project. The left plumber’s stance, gesture, and expression were highly directed, as the photograph shows. His features (evocative of silent film comedian Stan Laurel) and gestures are visibly more plastic in the painting.

Fig. 4. Unknown photographer, Reference photograph for Two Plumbers, 1951, cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, June 2, 1951, Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, ST1976.8035, ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5. Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), Two Plumbers, 1951, cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, June 2 1951, oil on canvas, 39 ¼” x 37”, Private Collection, ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

Perhaps because he intended the Four Freedoms project to embody high ideals, Rockwell qua cartoonist is occasionally absent from the famous quartet. No matter. Audiences who had been looking at his Post covers since the last World War embraced Rockwell’s amplified specificity, perhaps even filling in blanks, in the service of Roosevelt’s rhetoric.

The Paintings

The Four Freedoms did not run as magazine covers but rather as interior pages in the Saturday Evening Post, which collaborated with the US Department of the Treasury to distribute them. But all parties involved traded on Rockwell’s renown as a cover artist for the magazine to propel the project into the public eye. The modern Saturday Evening Post cover, as established most definitively by J. C. Leyendecker in the first decade of the twentieth century, consisted of a central motif, element, or scene suspended in a solution of negative space. No matter how adventurous Leyendecker’s later Post covers became, they remained almost militantly two-dimensional in spirit, resisting any urge to articulate a setting, or create a picture into which the viewer peered, as opposed to at which one looked. Norman Rockwell’s first Post covers followed the Leyendecker model, beginning with Boy with Baby Carriage (November 1917) and extending into the 1930s. Many of Rockwell’s finest covers of the 1940s and ’50s tackled ever more ambitious visual problems. The Four Freedoms help to mark the turning point toward more spatially ambitious pictures.

Fig. 6. J. C. Leyendecker (1874–1951). Baby New Year Charting 1933, cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, December 31, 1932, tearsheet, Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, RC.2010.19.3.65, ©1932 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN

Considered as a set, the Four Freedoms is an uneven affair that trades on Rockwell’s strengths but suffers from his weaknesses, albeit with the edge going decisively to the former. Freedom of Speech resonates yet condescends; Freedom from Want serves up the most satisfying aesthetic experience by withholding bounty; Freedom from Fear enacts Rockwell’s thematic squeamishness; and the weakest illustration, Freedom of Worship, domesticates its subject beyond all recognition, yet points to a future work, nine years on, that might qualify as the artist’s crowning achievement.

Freedom of Speech has justly remained a durable image, if one undermined by class condescension. Rockwell’s Post covers conveyed an amiable social cohesion grounded in the rituals of middle-class small-town life. We associate Rockwell with a communal world—implicitly placing the (admittedly homogeneous) group at the center. Freedom of Speech cuts another way, if only to a degree.

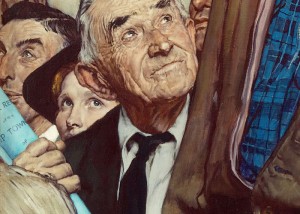

A Lincolnesque tradesman stands to state his case at a town meeting. His worn suede jacket, open-collared blue plaid shirt, casually rolled annual report, and workman’s hands mark him as anything but a cultural elite, to use today’s term. Tanned from outdoor work, the speaker stands in the visual center of four men. They are soberly jacketed and tied, comparatively pallid, implicitly professional. One has turned to listen to the remarks with wrinkled forbearance. Whatever his opinion, the townsman offers it plainly, without oratorical gestures. His gaze is upturned, mouth open, in a manner vaguely reminiscent of the saint in Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, suggesting a democratic apotheosis, an Everyman among the Gray Suits. Despite the patient reception, the likely result is clear: the professionals—better educated, more experienced in organizational affairs—are going to call the shots. With luck, our tradesman will have offered an unexpected insight that will inform their decisions. But he also might just be indulged and ignored. In either event, Everyman gets to say his piece. (Everywoman, less so. As Deborah Solomon notes in her biography of the artist, the painting “is compromised by a near absence of women, making it look . . . like a meeting of aging male Elks.” A facial fragment of a single female appears at the left margin.)[iii]

Fig. 7. Norman Rockwell (1894-1976), Freedom of Speech (detail), 1942, illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, February 21, 1943, oil on canvas, 45 ¾” x 35 ½”, Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRACT.1973.021, ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

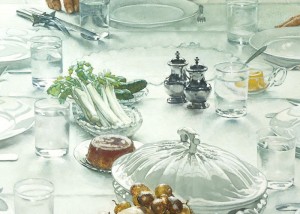

Endlessly parodied, Freedom from Want has entered that realm of images that signify themselves. Obscured by mental shorthand because it is instantly identifiable, the picture goes largely unseen. That is a pity, because Freedom from Want merits sustained looking. In abbreviated recollection, most recall a grandmother with a turkey and a family lining a table, which is true as far as it goes. Rockwell has stacked the people the way saints’ heads line the margins of an illuminated manuscript. The backlit presiding elders are positioned at the top of the painting, including the woman with the turkey—which upon examination might turn out to be made of Styrofoam for all it appears to weigh. (It is a casualty of Rockwell’s process. Almost certainly the model was photographed with a platter sans bird. We will never know, since the Arlington, Vermont, studio where Rockwell painted the Freedoms burned to the ground in May 1943, taking all his reference materials with it.)

The humans, then, provide the mass of the painting. If you squint, they form a warmly colored A-frame structure—a Sienese baldacchino—flecked at the bottom by a yellow-red bowl of fruit. But the people are not the subject of the painting. They may provide subject matter, but the picture has other fish to fry. It is about something else. When experienced in person, at scale, Freedom from Want is a painting about an austere feast, a celebration of light. Dramatic though it may be, the uncarved turkey seems to be it for food, aside from blanched-looking celery, an aspic, and some fruit. We confront empty plates and colorless water. No heaping bowls, no spilling cornucopia, no bottles of wine. But the restraint does not suggest self-denial—far from it. Rockwell paints an airy blanket of white light, sourced through the curtained window, that settles over the table, linens, china, silver, and glassware. Light suffuses everything, conferring grace on the gathering.

Fig. 8. Norman Rockwell (1894-1976), Freedom from Want (detail), illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March 6, 1943, oil on canvas, 45 ¾” x 35 ½”, Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRACT.1973.022, ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

Freedom from Fear offers formal comforts. A solicitous mother and tired, attendant father put their children to bed. The genre scene unfolds in an upper bedroom, the angle of pitched roof squeezing the picture from the upper left, complemented by the abbreviated diagonal of a stair banister on the right. Shapes in cascading light values spill down from the top: the man’s shirt, the woman’s (mostly obscured) white apron, an incipient horizontal slash of pillows, and a turned-down sheet. Next come the beige blanket and newspaper, and after them a set of blue gestures: a sword of skirt, the fallen doll, discarded clothing, a shard of dour wallpaper angling to an apex. Lastly, a satisfying notch, easily missed at the upper left: the corner of a framed devotional print—a throwaway in reproduction, surprisingly lovely in the original painting.

Rockwell’s methodology involved shooting the photographic reference for each character in turn, and Fear exposes some limitations of the approach. The suspendered father attends his wife, flanking her as she pulls up the sheet. Two abreast, like passengers in a car, each faces the head of the bed. All four feet line up, spaced evenly in pairs. The mechanics of this processional choreography are peculiar, in two respects. First, neither has room for hips. Unless they occupy space with the geometry of a pair of bedside tables, it is difficult to see how they could take up the minimal floor spaces assigned by their stances. Second, the woman bends over her children, leaning to the right over the bed. A figure so extended in one direction must make a corresponding adjustment in another to maintain her balance. Either her feet would be oriented differently, or her left foot would be stuck out to keep her from falling onto the bed. But her husband’s position prevents her from doing so. Had the two models posed together, subtleties of positioning would have prevailed. Their adjustments to each other would have affected the visual and spatial rhythm of the painting.[iv]

More obvious is an aversion to the putative subject of Freedom from Fear. Rockwell’s biographers (Laura Claridge; Deborah Solomon) have made much of the illustrator’s identification with Charles Dickens. The ruddy-faced boys and indulgent older men who populate Rockwell’s world justify such comparisons, as do his autobiographical writings. But the Dickensian Rockwell is incomplete; his illustrated world cannot accommodate a genuine threat, either pictorially or tonally. Nowhere will we find the villainy of Quilp or the wicked falsity of Uriah Heep, the bad guys of The Old Curiosity Shop and David Copperfield, respectively.[v]

I do not think it is fair to accuse Rockwell of lacking emotional range, exactly; at his best he captures longing, sadness, and pathos in addition to the impish joie de vivre we associate with him. But the personification of fear and danger were off the menu.

It is odd, really. Consider that other beloved mid-twentieth-century American melodramatist Walt Disney. He could scare the bejeezus out of his viewers, and routinely did; think of the near murder of Snow White and her headlong flight; the transformation of boys into jackasses in Pinocchio; the forest fire in Bambi; the hallucinogenic pink elephants in Dumbo. Nothing in Rockwell comes close.

Fig. 9. Norman Rockwell (1894-1976), Freedom from Fear, illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March 13, 1943, oil on canvas, 45 ¾” x 35 ½”, Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRACT.1973.020, ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

So it is, then, that the representation of fear boils down to a newspaper headline and an allegorically limp doll. Subtract the comforting genre scene and you are left with a lazily conceived editorial cartoon. Typesetting the words BOMBINGS and HORROR does not pack much punch. (See: Guernica, Picasso, Pablo.)[vi]

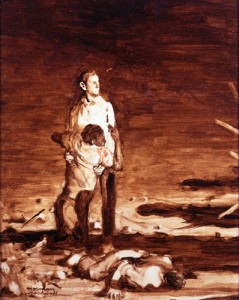

Even after Rockwell freed himself from the editorial strictures of the Saturday Evening Post and dug into civil rights themes for Look in the mid-1960s, he flinched. Murder in Mississippi, which depicts a moment just before the infamous killings of Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman in Philadelphia, Mississippi, on June 21, 1964, focuses on the victims, not the victimizers. An early sketch included a visualization of the threat, an extrajudicial posse led by Deputy Sheriff Cecil Ray Price. But Rockwell could not follow through. Save for their shadows, the killers remained offstage in the published work. (See: The Third of May 1808 in Madrid, a.k.a. The Executions, de Goya, Francisco.)[vii]

Fig. 10. Norman Rockwell (1894-1976), Murder in Mississippi (study), 1965. Illustration for Southern Justice by Charles Morgan, Jr., Look, June 29, 1965, oil on board, 16 3/16” × 12 13/16”, Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRACT.1973.079

Finally comes Rockwell’s attempt to illustrate religious pluralism, a subject fraught with cardboard peril. Unsurprisingly, Freedom of Worship brings up the rear of the quartet in all respects. Unlike the other three paintings, Worship is not situated architecturally. Fear and Want appear in domestic spaces, upstairs and down; Speech was staged in a public meeting room. Perhaps to avoid an ecclesiastical setting, thereby stacking the deck in favor of one faith over another, Rockwell creates a collage of heads in prayerful profile—a supplicant-as-sticker approach. A grandmotherly Protestant, perhaps flanked by her elderly husband, mostly obscured; a behatted Jew; a woman praying the rosary; a chin-stroking agnostic. Portraits in piety!

Spatially, dramatically, and thematically, the picture is a dud. Rockwell did not have a religious sense of life, and his pictorial translation of faith conveys nothing of the essential strangeness of religion. Despite the inevitable domestication of faith into liturgical procedure and moral injunction, at the heart of all religious experience lies bizarre wonderment: the unconsumed burning bush, the unspeakable YHWH, the revivified corpse of Lazarus, the New Jerusalem in outer space.

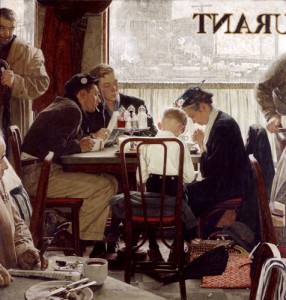

Rockwell would go on nearly a decade later to create Saying Grace, a vastly more potent take on private religion and public tolerance. It is arguably Rockwell’s very finest painting, and surely one of his best three or four works. That work, which appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post on November 24, 1951, forswore pietistic generalization and returned to the Rockwell wheelhouse: specific people and settings—or getting to the general by way of the particular.

Fig. 11. Norman Rockwell (1894-1976), Saying Grace, 1951, cover illustration The Saturday Evening Post, November 24, 1951, oil on canvas, 42” x 40”, Private Collection, ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

Rockwell gives us two travelers who have stopped to eat in a crowded restaurant somewhere in the northeastern United States. A slight grandmother and a small boy, by appearances Mennonites, are bent in prayer over a meal. Seated family-style across from them are two working-class tough kids, one dangling a cigarette and looking askance, the other scanning the room for other witnesses. As in Freedom from Want, white sunlight burnishes the dinnerware and cutlery, as well as the old woman’s faux-alligator bag, a particularly beautiful flourish when experienced up close. (The scene beyond the window is executed in graphite on unpainted canvas—a pencil drawing!)

Encircled by cigar smoke, this piety is properly strange. The quiet modesty of the devotional act in Saying Grace reminds us that some of our neighbors live in the world but refuse to think themselves of it. The Mennonites are Anabaptist cousins to the Amish. Into the 1950s they set themselves apart, too, if less radically. Rockwell focuses on his rakish onlookers, quizzical in the face of this private act in a busy, chaotic setting. They register disbelief but hold their peace. Rockwell shares their skepticism, yet honors the simple ritual of blessing food. I can think of no other picture that more intimately captures the sacred and profane in American life, while somehow celebrating both. Critically speaking, Saying Grace amounts to a back payment on the disappointing Freedom of Religion (even if Rockwell himself was quite satisfied with the latter).

Conclusion

Early in this essay I wondered whether an advanced cinematic economy in superheroes might amount to a kind of cultural sophomorism. I also suggested that Norman Rockwell’s melodrama suffers for want of the villains who populate his beloved Dickens. These are contradictory observations, which get to the heart of what is to be gained from a Four Freedoms revival now. What can Rockwell’s propaganda offer us in a national episode of unexpected ugliness?

Americans are having to relearn forgotten lessons. Chief among them are the disciplines of democracy, currently threatened by a decadent politics, too much money spent unaccountably by too few, and an immature communication regime of vast reach, traveling in disguise as technology. But we are still armed with a Constitution written by people who were deeply pessimistic about human behavior. They built a system designed to constrain the worst of it, with an extremely glaring exception. Under these conditions many people find themselves beset by temptations to Manichaean simplicity—good versus evil—even as they strain to keep George Orwell’s dictum top of mind: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.”[viii] How to stay attentive—to keep one’s lanterns lit—while staving off the deadly business of exhorting the infallible good guys against the irredeemable bad ones?

Perhaps Norman Rockwell offers a useful lesson about essential human decency, within historical constraints. Perhaps his disinclination to vilify and demonize may be put to good use. Call it conflict avoidance if you want, but Rockwell’s willingness to empathize with almost anyone is admirable.[ix] Good criticism, for its part, extends hospitality by seeking first to describe so as to understand. Too often we lack such generosity now, in part because audiences on social media prize quick judgment and colorfully phrased dismissals. Rockwell rewards the slower take, once prized in American laps in domestic spaces, of an encounter with an illustrated magazine.

Rockwell extends generosity to his characters and viewers alike, delivered through visual and dramatic attention to detail, complexity when necessary and simplicity when not, and sheer imaginative reach. If Norman Rockwell operated and created in a narrower (read: whiter) editorial landscape at the Post than we or he would have liked, in his way he made the circle bigger. He eschewed heroic generalization. He took people as he found them but improved them by investing them with an animated dignity. In his hands we are more charming, warmer, and possessed of more generous spirits than we are in real life. Now, to be sure, we must complicate this thought. Majoritarian myths are involved, appeals to sentiment, which tempt us to evade awareness of historical wrongs and to avoid fixing them. No elisions should be inferred. Let us not be untroubled.

But neither let us refuse a gift. Norman Rockwell thinks better of us than we deserve. If he abstains from the manufacture of villains, perhaps we can, too. We could grow into a Rockwellian sense of decency, extend it into places and spaces he could not reach or even imagine, and put it to work in the world. Such freedoms will be worthy of our devotion.

D.B. Dowd, Senior Fellow, is Professor of Art & American Culture Studies at Washington University in St. Louis, where he also serves as the Faculty Director of the D.B. Dowd Modern Graphic History Library.