Children’s Book Illustrators and the Golden Age of Illustration

by Corryn Kosik | Jun 26, 2018

Arthur Rackham, “Come, now a roundel and a fairy song,” Act 2 Scene 2, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare, 1908, pen-and-ink and watercolor drawing, 10 1/2 x 7″A common misconception is the idea that the Victorians invented childhood. Though there were obviously children running around and playing for innumerable generations before the 19th century, the concept of “childhood” was nowhere near as prevalent or as closely observed as it was by the Victorians. Children throughout history were often participating members of the household, assisting with daily chores which were commonly more labor intensive than making the bed or loading the dishwasher, in comparison with today. With the exception of children of nobility, there was no time for “childhood,” because the day-to-day activities were often necessary to stay alive. With the rise of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century, workhouses and mass labor added to the high mortality rate as men, women, and children were forced to work long hours in physically demanding jobs. Despite the impossible work conditions introduced during the Industrial Revolution and the hardship it brought to the working class, it also spurred many changes that led to the Golden Age of Illustration. Innovations in printing and engraving techniques meant that publications could be created faster and reach more people than ever before. The Industrial Revolution also created a larger, wealthier middle class, meaning that more people than ever before could purchase books, not only for themselves, but for their children. This newfound demand for books for children required authors and illustrators who were willing to create stories and illustrations solely for children, and this inspired artists in wholly new ways.

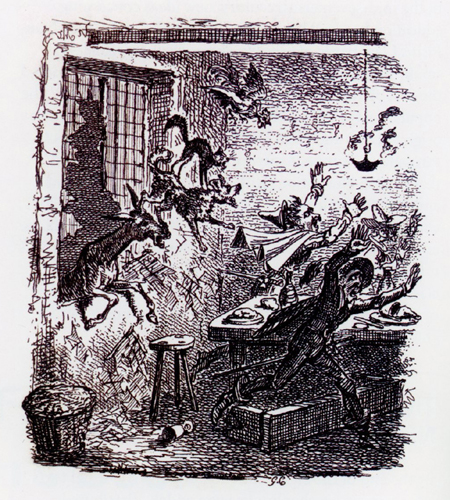

Before this creative enlightenment in children’s literature, publishers and disgruntled parents who couldn’t find anything suitable for their children to read, would often re-work and effectively censor fairy tales and nursery rhymes to present to their offspring. Many fairy tales that we know today as being “for children” originated as gruesome tales more appropriate for adults. Despite their censorship, late-18th and early-19th century fairy tales and nursery rhymes were still more violent than an average Disney movie, as they were often laced with heavily moralist values aimed at scaring children into becoming submissive, well-behaved young people. The arc of children’s literature and illustration begins in the late-18th century with George Cruikshank’s illustrations for German Popular Stories, the first time that a popular author deigned to create artwork for a children’s publication. Though many of his works, as well as those of other illustrators of the time, were heavily moralistic, works such as Edward Lear’s Book of Nonsense and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland illustrated by John Tenniel, helped to introduce children to the fantastical side of literature, showing them that books could be fun as well as educational. Today, scholars view George Cruikshank’s illustrations for the previously mentioned Grimm’s German Popular Stories as the beginning of the Golden Age of Illustration. Originally appearing in 1824, they were so popular that a second series was released in 1826. Though Cruikshank had great success as an illustrator, he was primarily known to his contemporaries as a cartoonist. Cruikshank’s work influenced many cartoonists and illustrators throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, making his career an apt milestone for the beginning of the Golden Age.

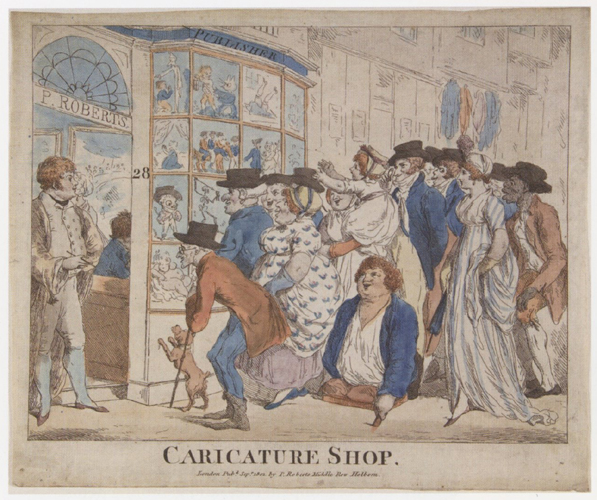

The 18th century was an opportune time for the rise of political cartoons and caricature because of the controversial characters in politics and the drama of the royal family. Satire was popular and cartoonists were able to openly ridicule the political and cultural happenings in a way that no one else could. The British political cartoonists were given far more freedom in this regard than any on the continent; Europeans who visited England were astonished at the liberties that British political cartoonists were granted with their mockery of political figures. Print shops within walking distance of the royal palace would place these caricatures in their windows and be patronized by the wealthy, but on some occasions, even royals and their officials would purchase the papers in which they were satirized.[1] Though most artists were from the middle and lower classes, many patrons of caricature were nobles. British caricature could not have had the freedom or success that it did if it had not been supported both financially and socially by the genteel classes. The majority of lower class viewers would have only been able to view the single-leaf prints of the cartoons and caricatures in the windows of the print shops, coffee houses, barbershops, and taverns [Figure 1] where they would have been posted for the public. Hand colored prints and full editions of the cartoons would have been available to be purchased by wealthier patrons, such as nobility and the royal officials previously mentioned.

Figure 1: Caricature Shop of Piercy Roberts, 28 Middle Row, Holborn, published by Piercy Roberts (British, active 1794-1828), 1801, Hand-colored etching, 10 7/16 x 12 ⅜”, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection Fund, 1953, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The era in which George Cruikshank (1792-1878) worked saw a particularly tumultuous period of political upheaval. William Pitt, the British Prime Minister in office from 1783-1801, headed an administration that saw many major defeats in the French Revolutionary Wars. Pitt also passed repressive legislation which limited the publishing of seditious material and the public’s freedom to criticize the king and his government. These laws would have especially affected George’s father, Isaac Cruikshank’s work, as he was a prominent political cartoonist in London from about 1783 until his death in 1811. It was Isaac Cruikshank’s caricature of Napoleon that served as the basis for George’s famous depiction of the soldier as a short man called “Little Boney” in an oversized bicorne hat. In one cartoon in particular, George Cruikshank shows him and his men buried in snow, Napoleon’s giant hat barely rising above the drifts. The inspiration for the cartoon was a failed maneuver during a Russian invasion from which Napoleon claimed he had planned to retreat.[2] [Figures 2 and 3]

Figure 2: Isaac Cruikshank, Buonaparte at Rome giving Audience in State, published by S.W. Fores, 1797, Hand-colored etching, 11 ⅓ x 15 ¼”, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Figure 3: George Cruikshank, Boney Hatching a Bulletin or Snug Winter Quarters!!!, published by Walker & Knight, 1812, Hand-colored etching, 9 ¼ x 13 ⅓”, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

The Prince Regent (later King George IV) was another of George Cruikshank’s prominent subjects for caricaturization, especially since he was frequently mocked by the people of Britain for his lecherous and indecorous behavior. George Cruikshank even galvanized the cause of the Prince Regent’s estranged wife, Queen Caroline, when she returned to claim her title as the Queen of England after having been driven back to her home country of Germany because of the king’s carousing. The King, eventually tired of being targeted by caricaturists, vainly attempted to prosecute them into submission. He eventually resorted to bribery and spent £2,600 in bribes between 1819-1822 paying off satirists and publishers; George Cruikshank himself accepted £100 in 1820 “not to caricature his majesty.”[3]

Shortly after the reign of King George IV, political caricature shifts to focus primarily on social satire and takes on a more respectable tone. The reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901) became one characterized by book illustration and satirical cartoons featured in the long running Punch Magazine. As stated in History of Illustration by Susan Doyle, “While satire and caricature had been powerful weapons against political corruption in the 18th century, by the second decade of the 19th century, members of the newly enfranchised middle class favored more naturalistic imagery and a more genteel approach to humor.”[4] Though Punch founders initially tried to steer the Magazine away from blatantly political cartoons when it launched in 1841, eventually political satire did make its way into the pages in the form of anti-Catholic (causing the resignation of Richard “Dicky” Doyle) and anti-Irish cartoons.

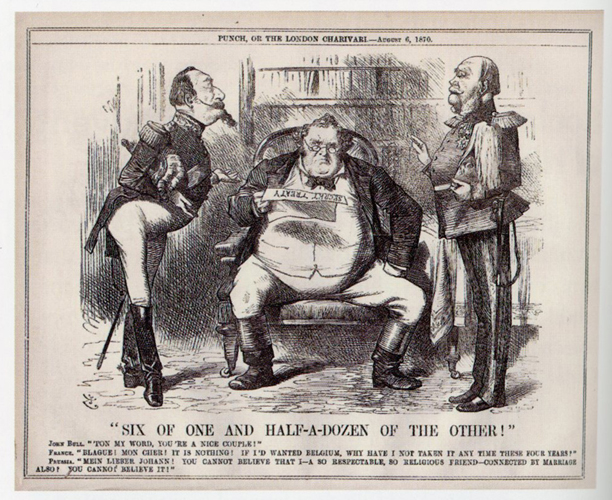

John Tenniel (1820-1914), like George Cruikshank, made a name for himself creating political caricatures. The Victorian influence of restraint is evident in his work, as he tended more towards naturalistic than theatrical figures. [Figure 4] Famous for his humorous, often anthropomorphized animal cartoons, Tenniel began working at Punch in 1850 and eventually worked his way up to principal cartoonist during his forty-three year career. Tenniel was knighted in 1893, honoring his long career at Punch and his important contribution to children’s literature in the form of his illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll. “Tenniel’s knighthood honored not only his work at Punch, but by extension validated visual satire as a vehicle for disseminating popular opinion in political discourse – a form once despised and feared by kings and politicians.”[5] Unlike King George IV who bribed Cruikshank not to publish seditious caricatures of the monarch, Tenniel’s knighthood from Queen Victoria was a figurative “seal of approval” of his profession as a cartoonist, giving endorsement to a once maligned occupation. Though this honor was an important symbol of the changing times, especially in printing and publishing, it was also an indication of how society and social commentary had changed between the reigns of King George IV and Queen Victoria, as Alice A. Carter states, “His [Tenniel’s] discretion yielded a half-century with Punch, and resulted in a knighthood for his moderating influence on political discourse.”[6]

Figure 4: John Tenniel, “Six of One and Half-a-Dozen of the Other!” Punch, August 6, 1870, From the collection of R.W. Lovejoy

Cruikshank and Tenniel, though their careers were largely defined by their caricatures and political cartoons, also made monumental contributions to the Golden Age of Illustration. According to Richard Dalby, the Golden Age began with the first English translation of George Cruikshank’s German Popular Stories, [Figure 5] published in two volumes between 1823-26.[7]This publication signaled a changing attitude in Britain towards folk and fairy tales when the German version was translated into English almost immediately after it was published. George Cruikshank’s illustrations most likely helped to increase sales of the book and the increasing popularity of fairy tales in Britain. Before the publication of German Popular Stories, children’s book illustrations tended to be static and lifeless rather than reflective of the lively characters Cruikshank created, which more often matched the spirit of the tales he was illustrating. His work set a new standard and created a framework for the illustrators to follow, such as John Tenniel and Richard Doyle (both would later become political cartoonists at Punch) who were directly inspired by Cruikshank’s work.

Figure 5: George Cruikshank, “Bremen Town Musicians,” German Popular Stories, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, 1823, Etching, Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books, Toronto Public Library

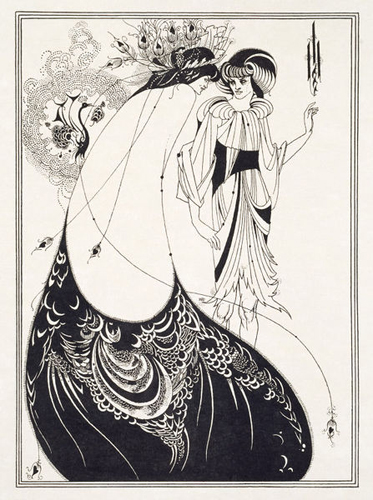

John Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in addition to the other publications he illustrated, seem to act as a literal visual description of the text. [Figure 6] Later on in the 19th century, some illustrators, such as Aubrey Beardsley, started to create images that complemented the text more so than illustrate it, visualizing the world described in the story, but not directly bringing the words on the adjacent page to life. [Figure 7] Tenniel’s illustrations follow the direction of the former, acting as direct accompaniment to the events happening in Wonderland. As a cartoonist, Tenniel was accomplished at telling a story in detail through his imagery, since he was tasked with representing the current events of his day through drawing. Many people believe that no other illustrator’s creations for Carroll’s beloved tales have surpassed that of Tenniel, “whose pictures appear in simple harmony with the prose, as if words and images were created by one hand to form the perfect union.”[8] Nearly fifty years later at the beginning of the 20th century, this opinion about Tenniel’s version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was still upheld, as Rackham received many dissenting opinions on his modernized illustrations for the story.

Figure 6: John Tenniel, “Off with Her Head!” Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, 1865, Wood engraving

Figure 7: Aubrey Beardsley, “The Peacock Skirt,” Salomé by Oscar Wilde, 1894, Line block print on Japanese vellum, 22.8 x 16.3 cm, Victoria & Albert Museum

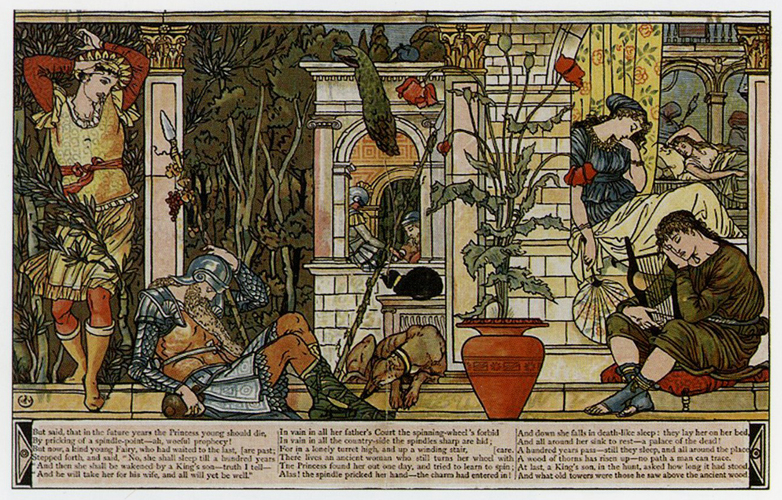

Building upon the high standard set by Cruikshank and Tenniel, Walter Crane (1845-1915) illustrated some of the greatest fairy tales and nursery rhymes of the 19th century in colorful children’s books. After being apprenticed to one of the greatest wood engravers of his time, William J. Linton, Crane began to work for Edmund Evans illustrating Toy Books* for Victorian children. A fervent socialist, Crane primarily worked on nursery rhymes, folk tales, and fairy tales, weaving a moralist lesson into the imagery of each one. Crane, like his mentor, became a gifted engraver, and after illustrating a plethora of children’s classics in sumptuous detail and color, became considered one of the greatest illustrators of children’s literature at the time. Unlike Tenniel, Crane took a great deal of inspiration from nature, because he looked to his friend and compatriot, William Morris, as well as the Arts and Crafts Movement, for stylistic inspiration. Like many Victorians, Crane began to think about the impact of formal education on children, and realized that his role as an illustrator of children’s literature placed him in a crucial position to enact change. Knowing that he could reach a wide, sprawling range of children with his illustrations, (especially since Toy Books were only considered successful by Routledge if they sold more than 50,000 copies[9]) Crane began to think about the ways that children absorbed information. He concentrated on the compositions, colors, and figural designs of his drawings to make them easier for children to read and appreciate.

The late 19th century saw the birth of the children’s book designed solely for children. As Gleeson White, the editor of famed Victorian arts quarterly The Studio writes, “…the tastes of children as a factor to be considered in life are well-nigh as modern as steam or the electric light…”, so writing and creating new stories and illustrations specifically for young minds was not a priority before the development of the “childhood” in the Victorian era. With the Industrial Revolution and the rising middle class came a new appreciation for the preserved innocence of children, and a sense of play and amusement that had not existed before. Thanks to new machinery, such as the steam engine, the sewing machine, and the cotton gin, manual labor was no longer the plight of every human being, and the newfound wealth of the middle class meant that more people could spend time and money indulging their children by purchasing toys and books. Though children’s books, were available in the late 18th century, they were primarily chapbooks** and fairy tales, such as German Popular Stories illustrated by George Cruikshank, that were not solely created for children, but rather transformed and often censored adult tales rewritten into children’s literature. “Even if the intellectual standard of those days was on a par in both domains, it does not prove that the reading of the kitchen and nursery was interchangeable.”[10] White’s statement in The Studio shows disdain for the literacy level of the adult in the late 18th century, stating that kitchen reading, or casual reading of low brow publications by adults, though simplistic in construction, was no substitute for children’s literature.

Though primarily known for his illustrations, Crane also assisted Edmund Evans, his longtime employer and partner in publishing, with the planning and writing of children’s alphabet and nursery books, such as Baby’s Own Aesop. Walter Crane, like many Victorians, began to take more interest in childhood education and the way children learned. He believed that children saw most things in profile, so many of Crane’s characters, both human and animal have very distinct facial profiles, reminiscent of the prominent features of many figures in Egyptian art, as well as the maidens featured in pieces by the Pre-Raphaelites. [Figures 8 and 9] Another distinguishing characteristic of Crane’s work is the bold, bright color and thick, dark lines which stem from his theory that children prefer “well-defined forms” and “bright, frank color.”[11] His images appear almost like stained glass with the thick lines functioning as the dark lead framework separating the pieces of colored glass. This comparison is appropriate considering Crane also worked in the decorative arts, and had designed opulent stained glass windows, wallpaper, and ceramics at different points throughout his artistic career.

Figure 8: Walter Crane, centerfold illustration for The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood, 1876, Xylograph, Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books, Toronto Public Library

Figure 9: Edward Burne-Jones, Laus Veneris, 1873-78, Oil on canvas, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England

Walter Crane’s brother, Thomas Crane, was also known for his involvement in the decorative arts, even re-designing the faҫade of Marcus Ward & Co. where he was the Director of Design. He also contributed many designs to the field of embroidery which was very popular for women of the Victorian era, as both a hobby for gentlewomen and as a means of decorating their homes. As Susan E. Meyer states in her book A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators, “In their cultural appetites, the Victorians displayed the same set of contradictions as they did in their moral deportment.”[12] Though they extolled the virtues of simplicity, they often decorated their homes in opulent Rococo-style decor; though they applauded the onslaught of the Industrial Revolution, they insisted on the importance of nature and purity. Although the Victorians were known for their restraint and prim demeanor, they were known for their love of scandalous railway novels, and their society also produced the ever-comical Edward Lear.

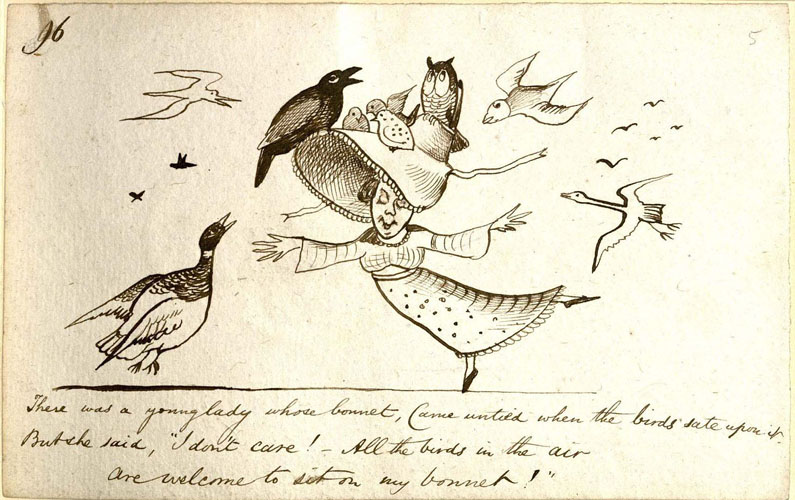

In contrast to Crane’s emphasis on educational values, Edward Lear (1812-1888), who had already published his scientific illustrated folios and his first Book of Nonsense by the time Crane was a year old, wrote simply to entertain children rather than instruct them. While Crane’s illustrations frequently accompanied fairy tales and nursery rhymes that often ended with a moral lesson, Lear’s Book of Nonsense series were, as the title suggests, nonsensical limericks. Originally a scientific illustrator, Lear began creating silly pen and ink drawings to make the children at Knowsley Hall (offspring of his employer, Lord Stanley) laugh. After receiving a book of limericks as a gift, Lear began to incorporate them into his drawings as a humorous complement to the caricatures, a combination which made the creations that much more hilarious to the recipients of the rhymes. Once published in 1846, the Book of Nonsense was revolutionary in the way it so blatantly contradicted the established structure of children’s literature. [Figure 10]

Figure 10: Edward Lear, “There was a young lady whose bonnet…” The Book of Nonsense by Edward Lear, 1861, Ink on paper, 21 x 29 cm, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Though Edward Lear did not create an immersive fantasy world like some of his contemporaries in children’s literature and illustration, he fashioned a place in the real world where children and adults alike could let go of the etiquette and constraints of polite society and simply laugh. His limericks and drawings were filled with nonsense, and it was exactly what Victorians of all ages needed at the time, as evidenced by the numerous praise it received, even from famed art critic John Ruskin. “Surely the most beneficent and innocent of all books yet produced is the Book of Nonsense, with its corollary carols — inimitable and refreshing, and perfect in rhythm. I don’t know of any author to whom I am half so grateful for my idle self as Edward Lear. I shall put him first of my hundred authors.”[13]

In contrast, Beatrix Potter and Arthur Rackham, who were working alongside one another at the end of the 19th and early 20th century, created magnificent escapes for their readers, children and adults alike. Playing into the Victorians interest in the natural world, Beatrix Potter’s anthropomorphized woodland creatures and Arthur Rackham’s fairies captured the imagination of children all over Britain and America. In many ways, the success of the two authors signaled the peak of the Golden Age of Illustration, and their continued popularity two hundred years later is testament to this idea.

Like her contemporary John Tenniel, Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) created a Regency-era utopian world for children that provided an escape in her books. Potter, taking inspiration from her surroundings, created the words and pictures for an idyllic world in which animals played, and made mischief like humans, and illustrated it in great detail. Like Walter Crane, she put thought into the design of her books, which is unsurprising since she paid to print the initial run of 250 copies herself. After this first independently printed edition sold out, Frederick Warne & Co. began to represent her and asked if she would illustrate the books in color. The beautiful watercolor illustrations that the world has come to associate with Beatrix Potter are now almost synonymous with children’s literature. The delicate pastels of Peter Rabbit’s jacket and Jemima Puddle-Duck’s shawl and bonnet are a reminder of childhood and daydreams of the pristine countryside. [Figure 11] The precision and detail in her watercolors was borne out of experience creating scientific illustrations en plein air, though the layout of her text was simply taken from her experience with children.

Figure 11: Beatrix Potter, “Now run along, and don’t get into mischief. I am going out.” The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter, 1901, Watercolor and ink on paper

As can be seen in her letter to Nӧel (the son of her former governess, Annie Moore), in which she first wrote what would later become Peter Rabbit, Potter knew that a few lines of text were all that children could easily associate with an image. Each of her watercolors has its own page (recto, or front) while the corresponding few lines of text is on the facing (verso, back of the previous) page. Though Potter clearly took children’s methods of learning into consideration, her designs and style are quite different from Walter Crane’s. Whereas Crane used wide blocks of color, thick outlines, and two-dimensional space in his illustrations, Potter’s artwork is much more delicate, with thin wispy lines like those of Randolph Caldecott, and detailed colorwork that made the most use of light, pastel colors. Arthur Rackham, like Beatrix Potter, also preferred to work in watercolor with thin lines to create detailed, moving figures.

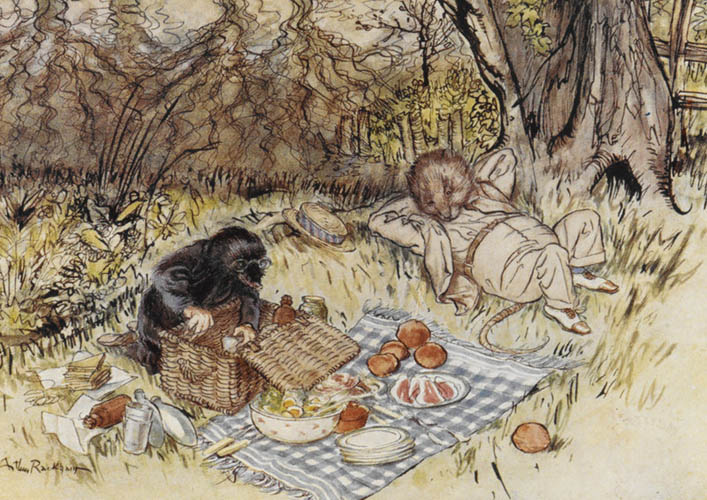

Arthur Rackham’s career (1867-1939) was the culmination of the Golden Age of Illustration in Britain. With a career that stretched from the late 19th to early 20th century, Rackham produced some of the most memorable illustrations of the era for beloved children’s classics. Like Crane, he tended to primarily work with fairy tales and nursery rhymes, but also illustrated folk tales such as Rip van Winkle, which made a name for him in the early stages of his career. Rackham became known for both the beauty and repulsiveness of his figures, from his famous fairies first depicted in “Fairies of the Serpentine” from Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, to his crotchety crones and gnarled trees as in “Major Andre’s Tree” from The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Like Walter Crane and Beatrix Potter, Rackham’s illustrations were often heavily tied with nature, a prevalent interest for many Victorians at the time. [Figure 12] An awareness of the natural world was making a resurgence as society was rapidly becoming mechanized; members of the Arts and Crafts Movement and those interested in the art of the Pre-Raphaelites were attempting to reconnect with the steadily industrialized world around them through art and literature.

Figure 12: Arthur Rackham, Image from A Wonder Book by Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1922, Watercolor and ink on paper

Rackham became the most famous illustrator of the late 19th and early 20th century and set yet another standard for children’s book illustration with his sepia-tinted watercolor and ink drawings. Like the appearance of Cruikshank’s lively engravings for German Popular Stories nearly a century earlier, Rackham’s watercolors brought new life and color to illustration. The innovations in printing during Rackham’s career helped to make strides in the field; Carl Hentschel, an English printer, developed a process called Colourtype which he applied to Rackham’s illustrations. The printing method meant that only heavier, glazed paper could be used for the printing, but it also meant that all of the detail and rich color in Rackham’s work would be evident in the prints. This was clearly seen as a worthwhile endeavor. In order to help fund this more expensive printing process, William Heinemann, Rackham’s publisher, began working with Leicester Galleries in London to sell the original drawings by Rackham for each book that was published. This arrangement first took place in 1905 when Rackham completed his work on Rip van Winkle, which sold all but eight of his original drawings. This sales opportunity became the norm for all of Rackham’s illustrations afterwards, and was even implemented during Edmund Dulac’s career, which paralleled Rackham’s for a period of time. While this opportunity was financially beneficial to Rackham’s career, it also helped to elevate illustration to the level of fine art. Exhibiting original illustration work as limited editions in a prestigious London gallery was beneficial to all illustrators during the time, and has had a lasting impact on the medium since.

Illustration began to be collected like fine art. Gift books, which had been popular throughout the 19th century, reached a new level with deluxe editions filled with Rackham’s illustrations. These gift books were ostensibly created as holiday presents for wealthy children, and on a number of occasions throughout the late 19th century, it was said that Rackham’s new gift book was the present to purchase that year. These books were often viewed as collector’s items which added to their exclusivity and their demand among rich Victorians. Rip van Winkle was the first of these that Rackham illustrated, and it established him as the leading decorative illustrator of the Edwardian period, with many additional gift books to follow. J.M. Barrie commissioned him to illustrate Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, which further elevated his prestige as an illustrator, and from then on he only increased in popularity throughout the next decade.

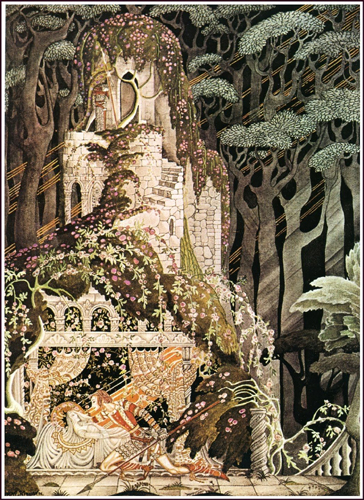

By World War I, book production and the market for fine gift books was suffering and did not recover, and the sales from Rackham’s 1919 exhibition at Leicester Galleries were disappointing. Though he continued to produce a new children’s book every year through 1920, the British market was waning, so Rackham traveled to the United States where sales of his books were surpassing those in his home country. Despite continuous book sales on both sides of the Atlantic, the sales of deluxe gift books were much lower than they had been previously, and this movement away from expensively produced lavish volumes did not show promise of resuming anytime soon. Rackham still received a great deal of illustration work, but book production had become focused on modestly produced editions, and the market for luxury children’s books never recovered on either continent. Though this made it difficult for many illustrators who had previously illustrated deluxe editions, Rackham’s ability to continue illustrating was fortuitous since others were forced to look elsewhere for employment. Edmund Dulac, a contemporary and one-time competitor [Figure 13], was also able to illustrate books benefiting the war effort, however Kay Nielsen [Figure 14] turned to set design and decoration, eventually working for Walt Disney in the late 1930s. Rackham continued to illustrate until his death in 1939, the year in which he completed his last commission for The Wind in the Willows [Figure 15]. Though the Golden Age of Illustration, begun in the early 19th century, had largely come to an end in Britain, the work of Rackham and the eminent illustrators who came before him would continue to influence and inspire children’s book illustrators for generations, including many American illustrators.

Figure 13: Edmund Dulac, “She played upon the ringing lute, and sang to its tones.” The Wind’s Tale in Stories from Hans Andersen with Illustrations by Edmund Dulac, 1911, Watercolor and ink on paper

Figure 14: Kay Nielsen, Illustration for La Belle au Bois Dormant by Charles Perrault, 1913, Ink and watercolor on paper

Figure 15: Arthur Rackham, “Rat and Mole having a picnic,” The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, 1940, Watercolor on paper, British Library

The Golden Age of Illustration spanned nearly two hundred years of writing and illustration, with many talented artists leaving their lasting mark on the genre. It is clear from the illustrators’ careers and their artwork that the cultural landscape in which they lived was an integral influence upon their creativity. From the political cartoons and caricatures of the late 18th and early 19th century to the development and subsequent evolution of children’s stories, the changes in themes follow the arc of the social and political developments of the time. Key among these factors is the Industrial Revolution which affected printing innovations and served as a catalyst for the rising middle class, who with their hard-earned money, were eager to dote upon their children by purchasing children’s books. American illustration was following on the heels of British illustration, and as innovations in printing and design made their way across the pond, American illustrators such as N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, and Norman Rockwell contributed to the Golden Age until its end in the early 20th century. The Golden Age of Illustration set the stage for the future of children’s books, both in relation to content and imagery. They began the work of making children’s illustration a respected art form, and made strides to proclaiming illustration as significant as fine art.

[1] R.W. Lovejoy, Chapter 11, “Dangerous Pictures: Social Commentary in Europe, 1720-1860,” in History of Illustration (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018) 175. [2] R.W. Lovejoy, Chapter 11, “Dangerous Pictures: Social Commentary in Europe, 1720-1860,” in History of Illustration (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018) 177. [3] R.W. Lovejoy, Chapter 11, “Dangerous Pictures: Social Commentary in Europe, 1720-1860,” in History of Illustration (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018) 178. [4] R.W. Lovejoy, Chapter 11, “Dangerous Pictures: Social Commentary in Europe, 1720-1860,” in History of Illustration (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018) 181. [5] R.W. Lovejoy, Chapter 11, “Dangerous Pictures: Social Commentary in Europe, 1720-1860,” in History of Illustration (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018) 183. [6] Alice A. Carter, Chapter 16, “British Fantasy and Children’s Book Illustration, 1650-1920,” History of Illustration (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018) 252. [7] Richard Dalby, The Golden Age of Children’s Book Illustration (London: Michael O’Mara, 1991) 9. [8] Susan E. Meyer, A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987) 65.* Toy Books were short, inexpensive children’s books popular during the Victorian era. Edmund Evans revolutionized the market for Toy Books when he hired Walter Crane, and began producing very large print runs for the first editions, often more than 10,000.

[9] Humphrey Carpenter and Mari Prichard, The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984).** “Chapbooks were small, affordable forms of literature for children and adults that were sold on the streets, and covered a range of subjects from fairy tales and ghost stories to news of politics, crime or disaster.” Ruth Richardson, “Chapbooks,” Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians, British Library, May 15, 2014, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/chapbooks.

[10] Gleeson White, “Children’s Books and Their Illustrators,” The Studio (London: Offices of the Studio, 1897) 72. [11] Susan E. Meyer, A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987) 88. [12] Susan E. Meyer, A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987) 12. [13] Susan E. Meyer, A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987) 58.