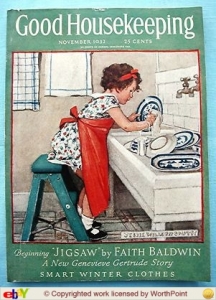

Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935) | Girl Washing Dishes, 1932 | Cover illustration for Good Housekeeping (November 1932) and again for the British edition of the magazine (January 1933)

Between the late teens and March 1933, Jessie Willcox Smith created nearly 200 illustrated covers for Good Housekeeping magazine.* Interestingly, from March 1920 through November 1932, she produced four Good Housekeeping cover illustrations of children doing things that included images of Chinese influenced blue and white china. In the above November 1932 cover illustration, for example, a young girl wearing an over-large red apron, stands on a folding green step stool and leans over the white porcelain kitchen sink washing Blue Willow patterned china. Hanging on an unseen towel rack beside her are two blue and white linen towels drying.

Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935); The Epicure, 1908; illustration for Carolyn Well’s poem, “The Seven Ages of Childhood” published in The Ladies’ Home Journal (November 1908)

Possibly the first time Smith used Blue Willow patterned china as a component her visual story was in the image of The Epicure created as one of a group of illustrations that accompanied Carolyn Well’s poem, “The Seven Ages of Childhood,” in the Ladies Home Journal, November 1908. The following year the poem and illustrations were published as a book by the New York firm of Moffat, Yard & Co.** The illustration shows a close up view of a young girl seated at a white linen-covered table eating a large bowl of porridge. The bowl and the plate underneath it are Blue Willow pattern as is the larger plate to the child’s proper left that holds a piece of bread. In front of the girl sit a tiny doll and a larger clothed stuffed brown bear. Behind them, resting at the top ledge of the wainscoting of the dining room wall are two more larger blue and white platters.

By the end of the 18th-century Blue Willow patterned china was being produced in England by Coalport China and by Spode. American versions of this same pattern followed in both china and earthenware.Willow patterned dishes feature a beautiful Chinese home with a willow tree leaning over near a small bridge that has three figures hurrying across, a humble servant’s house is across the bridge, in the water a small Chinese boat floats and birds fly above the willow tree. The many versions of this pattern are seen mostly in blue and white, but they also come in red, green , and brown transferware colors.*** The pattern has even been produced on glassware, wallpaper, tablecloths and towels, soap dishes and paper napkins.

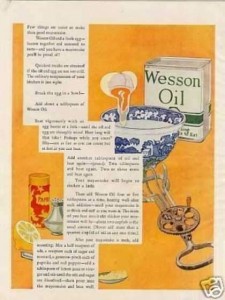

So why did Jessie Willcox Smith use Blue Willow pattern dishes in her illustrations? Perhaps her use of the distinctive patterned dishware was due to it’s recognize-ability. There were dozens of manufacturers in England and America from the late 19th through the early 20th centuries who produced Blue Willow pattern dishes including the restaurant supplier Buffalo China. So common were Blue Willow dishes that in the 1920s magazine advertisements for Wesson Oil also used Blue Willow pattern dishes as part of their ads about making things with oil, as seen below.

Wesson Oil magazine advertisement, 1925; found on Vintage Ad Browser 5/1/2012, https://www.vintageadbrowser.com/food-ads-1920s/33

In 1940, the American children’s book librarian and author Doris Gates published her popular story, titled Blue Willow, about a poor little girl whose family are migrant workers.*** It is the picture in the Blue Willow plate that once belonged to her great-great-grandmother, that is the dream home the girl wishes her family could have as their permanent home.

Collecting and displaying Chinese-made blue and white wares was also a popular past-time in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Artists like the American James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) admired and collected fine imported Chinese pieces, and in 1876-77 he decorated Englishman Frederick Leyland’s Peacock Room dining room created by Thomas Jeckyll to display Leyland’s collection of Blue and White porcelain. In America too, collectors often displayed their fine blue and white porcelain plate collections resting on a wainscoting ledge as pictured in Smith’s above illustration.

The ubiquity of usage of these patterned plates among the middle class and upper classes was, in a way, explained by the exoticism the Chinese scene represented. In the 19th and early 20th centuries Americans and Europeans were entranced by products from the Middle East and from East Asian cultures. Orientalism, the interest in those cultures and their products, exploded beginning in the 17th century with the arrival of Chinese trade goods in European and American markets. Soon American and European craftsmen and potters attempted to recreate Chinese themes and styles in decoration, form, and quality.

* Good Housekeeping paid J.W.S. between $1,500 and $1,800 for each cover illustration. This information comes from Edward T. James, ed., Notable American Women, 1607-1950 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, The Belknap Press, 1971). Today that $1,500 would have the purchasing power of about $15,000.

** The Ladies Home Journal illustrations were printed in black and white, but when the subsequent book was published the illustrations were printed in color. See https://archive.org/stream/sevenagesofchild00well2#page/n7/mode/2up The segment of the poem on The Epicure was titled, “Then the Epicure; With fine and greedy taste for porridge.” The verse later continues,

In tones that leave no room for doubt

She intimate she is unable

To eat her bread and milk without

Her bear and dolly on the table.

*** Created like a print on paper, transferware refers to ceramics whose surface decoration is applied by an engraved print transferred to a wet inked tissue paper and then onto the ceramic surface before it is given low-fired kiln baking.

**** There are a variety of fictional stories associated with the Willow pattern design including poems, a comic opera, a silent film, and a Chinese detective novel. Gates’ Blue Willow is the first story book I remember reading in my Detroit school’s library in the mid-1950s.

September 6, 2012

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum