Episode 02: Louis Henry Mitchell

Welcome to The Illustrator’s Studio. I am Jesse Kowalski, Curator of Exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The Illustrator’s Studio is a weekly interview series, a project of the Museum’s Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies. In this episode of The Illustrator’s Studio, we welcome Louis Henry Mitchell, Creative Director of Character Design at Sesame Workshop, the home of Sesame Street. A lifelong fan of the Muppets, Louis actually began his career illustrating for comic book legend Neal Adams. Louis joined the staff of Sesame Workshop in 1992 and in 2000 he was hired in a more senior role, and he has never left. Louis, welcome to The Illustrator’s Studio.

Thanks Jesse. So glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

Yeah. So you and I met last summer, Summer 2019. I was curating an exhibition on illustration in the year 1969, because that was the year… it was the 50th anniversary of the Norman Rockwell Museum and the 50th anniversary of Sesame Street, of course.

Absolutely.

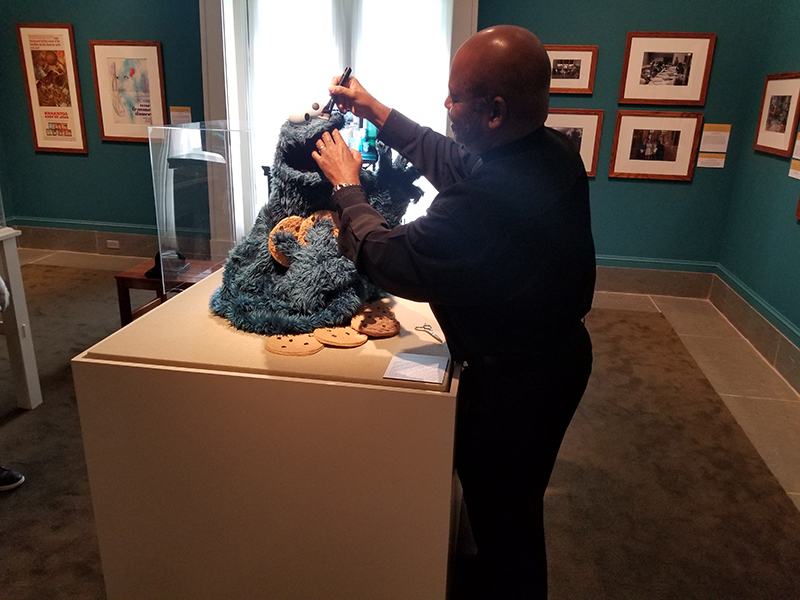

Sesame Street and the Muppets have been a big part of my life, and so that’s why I wanted to include a larger section in the exhibition. And I really wanted to have a Muppet there, and so we were lucky enough to get Cookie Monster in the exhibition. Yeah. So you traveled to the museum, you came here with your grooming kit, right? And you fixed Cookie Monster up and… you know, instantly, I just thought you were such a great guy and, you know, you cared so much about your job and everything. And I remember when you got to the museum, you know, you had this light in your eyes, like you were really happy. So what was going through your mind when you got to the Rockwell?

Well, he means so much to me. There’s really no way to describe it. And since I’ve become a member of the Board of Trustees, the interest and the love has grown even further because there are so many things I discovered about him. But the thing is that when I was sixteen years old, I went to the bookstore and saw this book. It was the Norman Rockwell book, Norman Rockwell: Illustrator, not the big one, but the smaller one by Watson-Guptill. And I was just flipping through quickly… I couldn’t believe my eyes. It wasn’t that they looked photographic, they looked like they were really there. I mean, it wasn’t like a photograph. It was like a human being in the book. And I just fell in love with him. And that was very early on in my… maybe the second week of high school. I just saw it, and that was it. So to be able to walk into the museum and see those original pieces of artwork, there’s nothing like seeing the originals, it’s beautiful to see the covers and the pictures in the book, but to actually walk up, and you can’t get too close… I mean, I’ve been asked to step back a couple of times, and I don’t mind because again, I’m trying to be respectful, but those are sacred artifacts. Those were, those are pictures that molded me as an artist because Mr. Rockwell just means so much to me.

Now, were there any specific artworks that stand out for you?

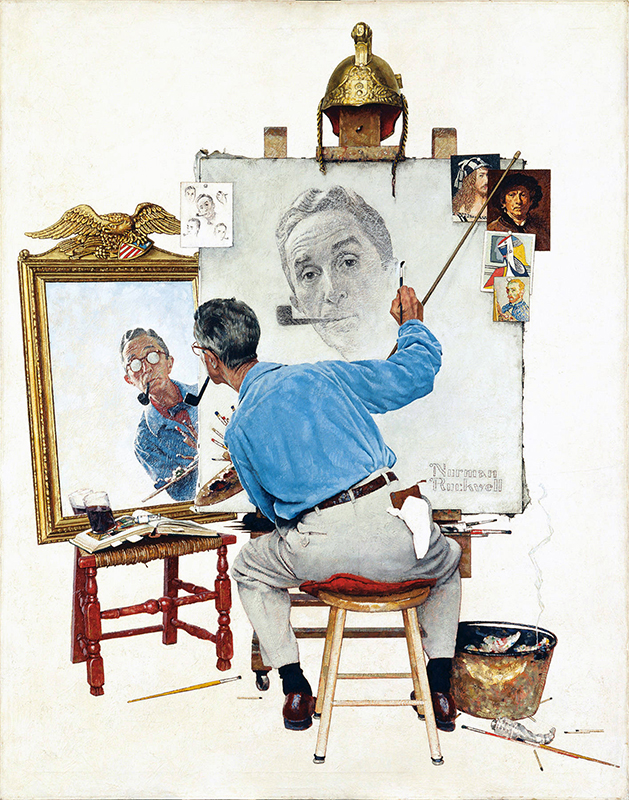

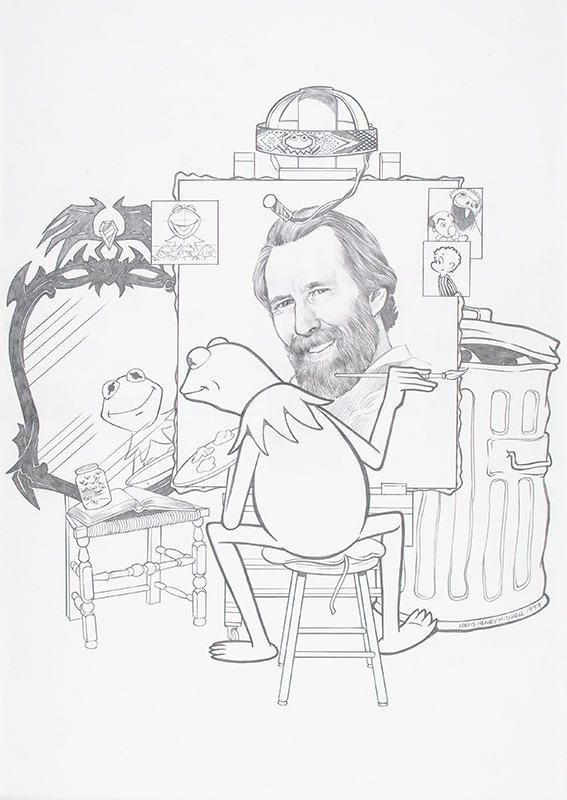

Wow. That’s uh, well, I guess the one that really touched me the most was the Triple Self-Portrait. It’s my experience. Not that I think it’s the best of all of his paintings. How do you do that? But it depicts him. It’s a self-portrait of him. Actually, it’s not a triple self-portrait, because up in the corner, there are, I don’t know, I think, five little sketches in that little piece, but no, it’s just that the way he depicted himself there. So that’s why… remember that drawing that I did, kind of an homage to that drawing, as the artist looking in the mirror and drawing Jim Henson.

So you mentioned you’re on the Board of the Museum now. We’re so thrilled to have you, you know, you’ve got such a great mind and so much enthusiasm. It’s perfect having you there. What kinds of things do they have you working on?

Well, one of the most exciting things was, I mean, of course I love to attend the meetings that we have, but, Stephanie Plunkett, the Chief Curator, she’s just a wonderful, such a wonderful person and a dear friend now, but she actually asked me if I would write a blog. And then she asked me if I would write a couple of commentaries for paintings in the gallery. And I said, “You want me to write?” Of course, I just put my heart and soul into it. And she loved what I had done. So, but the thing is when I did the… she sent me a lot of research material, which I was so… of course the curators are going to have all this wonderful, this fodder, for me… but I learned that Mr. Rockwell was a member of the NAACP.

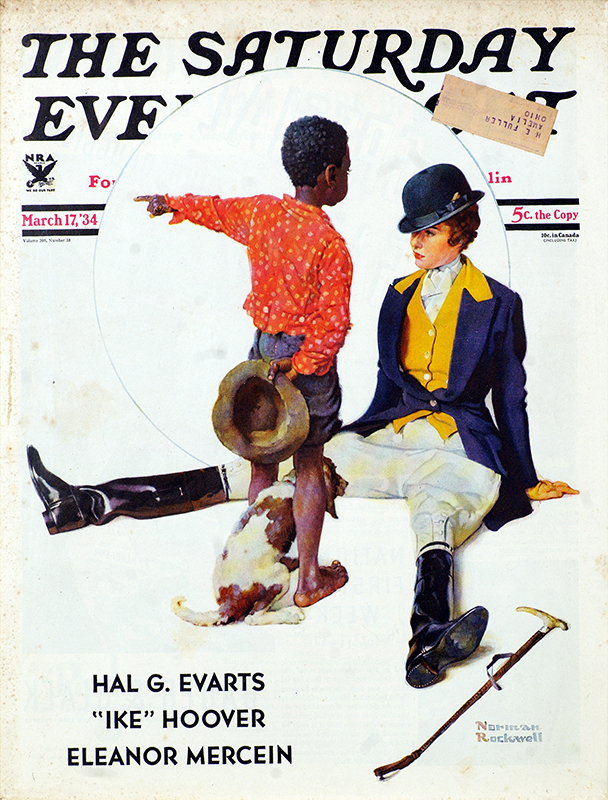

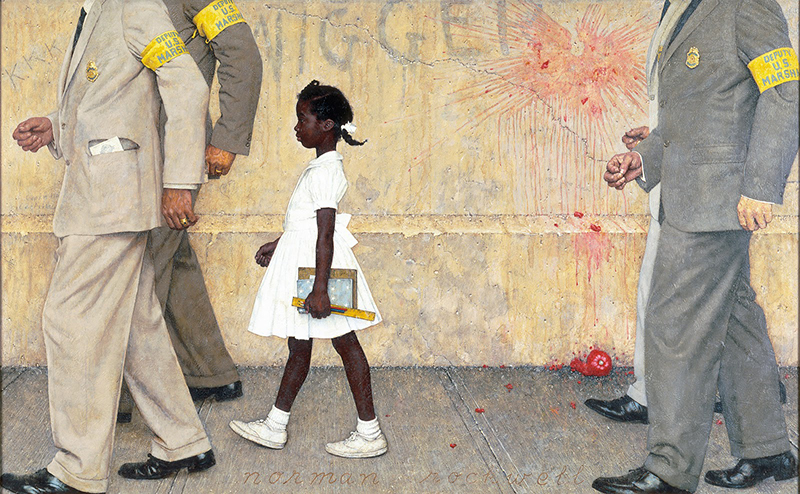

Now, the thing is, I did not know he was a life member. All the things I knew about Norman Rockwell, I have virtually every book, I have files, I have so many things, I have videos… I didn’t know that his commitment was that to that degree. And of course, when he was doing the paintings for The Saturday Evening Post, he wasn’t really allowed to show people of color. You know, I mean, every now and then he was able to get something in. I think the first one had to do… I forgot the date, but it was a little boy… A woman had fallen off her horse and he was standing over her pointing the direction where the horse went. I think that was the first time he actually was able to get a person of color. And the thing is once he left there and he started, you know, in the ‘60s, he just exploded and started doing all these… you know, the Ruby Bridges painting…

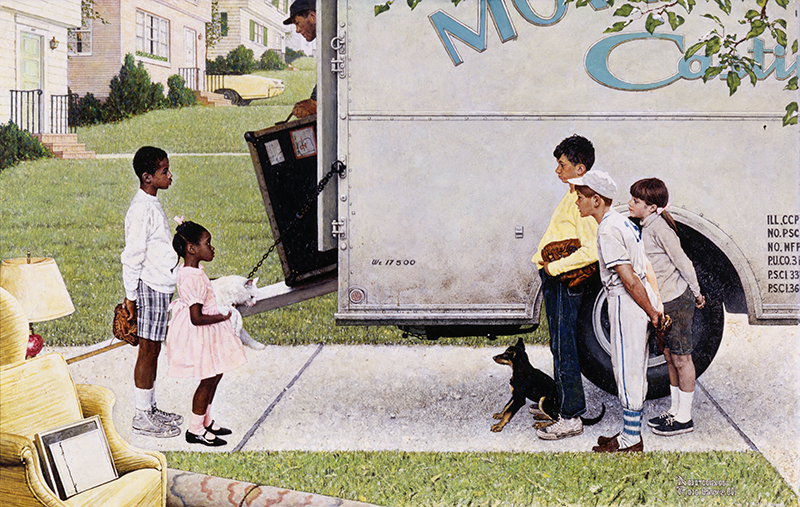

The Problem We All Live With, I think is it… just so many things that he did. And I said, well, that’s really something. When I found out that he was a member of the NAACP, one of the… I have considered five people my mentors: it’s Martin Luther King, Jr., Norman Rockwell, Jim Henson, Leonardo da Vinci, and Leonard Bernstein, but the two key ones in there are Dr. King and Norman Rockwell… the first two. They were… Norman Rockwell became a member of the NAACP at the same time Dr. King was affiliated with it. So I didn’t know that. So she, and I asked her if I could have permission to write an additional commentary focusing on that, because people need to know, you know, that right now the museum is creating initiatives and programs and even shows that kind of talk about inclusion and, you know, talk about how racism has no place really on this planet.

And sometimes if people look at Mr. Rockwell’s work, they would think that he wasn’t really into it that much. Because he painted anybody who was pretty much, you know, white, but the thing is that he wasn’t allowed to. But the minute when he was free to do that, he celebrated people of all nationalities. But in that particular case, it was just so exciting for me to find that he was a member of the board – that made it legitimate. So whatever we do at the Museum, it started with him and his commitment to the NAACP and to humanity at large.

Oh, that’s great… so, how old were you when you first saw the Muppets perform? It was on The Ed Sullivan Show, I believe?

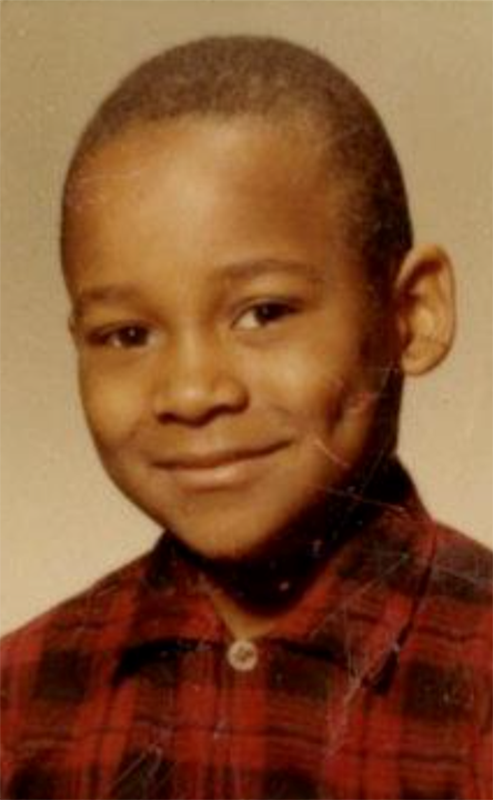

The Ed Sullivan Show. I was six years old. Now, I was about a month away from becoming seven, and I was six years old. And actually that’s why my sixth mentor is me when I was a… I’ll see if I can get a good… That’s me, when I discovered Jim Henson on The Ed Sullivan Show. And that’s why I keep that, because I remember that moment so well. And the whole thing is that I heard the Muppets so many times, and whenever someone would say, “Hey, here come the Muppets!” And so I would run and watch the TV, but this one time he had Kermit. Kermit was like playing the piano and there was just this monster on the side. I think eventually the piano became a monster that ate him, but afterwards, Ed Sullivan kind of gestured to come to him. And Jim Henson came to him. And he’d done that many times before, but this time he had Kermit on his hand. And that was it. That’s what changed my life. That’s… you mean a man was doing that? And my head spun into this wonder world that never stopped till this day, and led me to where I, you know, where I am now.

What do you find inspiring about the Muppets?

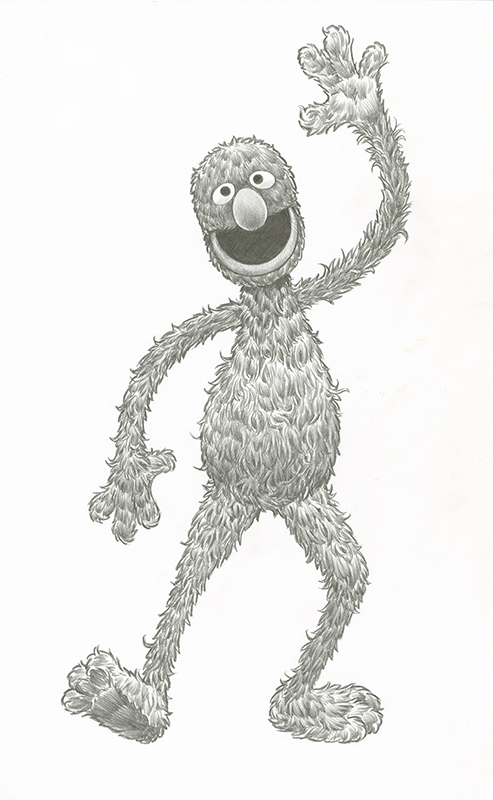

Oh my goodness. Well, you know, the more you know about the Muppets, the more you start to see that they… each one of them represents, especially the Sesame Street Muppets, not exclusively, but especially those Muppets. Because again, when I teach character design, to people all over the world, because I have to train people all over the world because you know, we have so many multiple co-productions that they have to learn how to… Elmo is in almost every co-production. So they may have their own walk-around Muppet, but Elmo, Grover, Bert and Ernie… are usually ones that are in their co-productions as well. So whenever they have to reproduce artwork, they have to be consistent with the way we’ve established them. So we, like, teach them how to do that. But I don’t think it’s so much how to draw them – I teach them who they are. So the thing is that they really embody the purity of an emotion.

Like Elmo is all about unbridled enthusiasm. He’s always inquisitive. He wants to explore everything. He’s so excited about life. You know, Cookie Monster, my favorite one of all… as passionate as he is about cookies, he would give his last cookie to his friends. And most of his friends want a cookie. So that means you can be passionate about something, but you don’t have to be a jerk. You can be a loving, you know… my favorite one to teach though is Grover because Grover, no matter how many times he makes a mistake, he will never… he’s never down on himself. He never stops to say, “Oh, I’m stupid. I made a mistake.” He never ever does that. The only problem is that he only makes mistakes. Everything he does is a mistake, so thank goodness he’s not down on himself. But these are things that show kids, you know what these are…

I mean, we’re not really making them perfect examples, because they are cartoons in some cases, puppets… but they do kind of send a signal to a kid, like Grover saying, “Don’t ever be down on yourself. Just keep on trying.” He adds a sense of humor to it, but kids learn. You know what? It’s like Cookie Monster. Yeah, I have a cookie, but I’m going to share it with you. I love cookies so much, but I love you more, so here, have my last cookie. So it’s teaching kids, you know, about how to be excited about life, but how to also be a loving human being.

That’s excellent. Wow. Could you tell me a little bit about your childhood and kind of how you grew up and developed into someone who is now one of the main creative forces at Sesame Street?

Oh, thank you. It’s nice hearing that. Well, I attribute every single bit of it to my mother. Now my poor mom, I shouldn’t say my poor mom, but I was a pretty sweet kid, but pretty quiet. But when I saw Jim Henson and that… now I followed Paul Winchell. He’s another ventriloquist, you know, a puppeteer, and I loved his work. I loved Topo Gigio. He was also on The Ed Sullivan Show. Um, I loved Kukla, Fran, and Ollie. I’d seen other puppets. Um, oh, what’s his name? Um, Chuck McCann was a man that was back in the ‘60s. I think in the ‘50s as well. And um, I can’t remember the name of the… oh, Paul Ashley, Paul Ashley Puppets. Beautiful, beautiful puppets. All exciting. But it wasn’t until I saw the Muppets. That’s when that thing happened to me. So my mother saw that something clicked and she didn’t know how exactly to help me, but she just immersed me in anything that I wanted to do after that.

Of course, it was all about drawing and puppets, you know, music and things like that. You can see a piano back there. I taught myself how to play the piano because a girl broke my heart in junior high school. And I wandered into the music room and just started figuring out Elton John songs. It just kind of happened. And I asked mom if she would buy a piano, I had never told her that I was learning. She said, “Why do you want a piano?” I said, “Well, mom, it’s because I just love piano.” She said, “I can’t afford a piano.” Little did I know that when I walked away, she made a deal with the piano guy, the piano store guy. And I come home one day and the piano was there. So it was really because of this great mom that I had that, she passed away about three years ago, but she was ninety-eight years old.

It was on her terms. So she had a full, beautiful life. She got to see me achieve my dream job. And again, I was told a lot by other people I wasn’t going to make it, but she said the one thing she always said, “Don’t pay attention. Just keep going. Just keep going.” That’s all I needed to here. So even though I was kind of a shy kid, um, I really remember when she said that. So whenever somebody told me I couldn’t do something, even though I might’ve heard it, but I didn’t let it stop me. I just kept going. Like she says, as a matter of fact, I even have a note I keep on my desk here. That from my mom’s statement, “Just keep going.”

Wow. She sounds like an amazing woman. And it sounds like you’re really carrying on the tradition of building up self-esteem in children, and it’s really wonderful.

Well, the thing is the kids, you don’t have to build their self esteem. You have to protect it because they already, they have a sense of… that they’re special already. And people start to chisel away at that. And that’s usually what we see when people start telling children, “You can’t do this and you can’t do that.” And that happens a lot in a lot of kids. You know they have this voice. To me, like you saw that picture of me when I was six years old. That’s still me. And thank goodness my mother protected me back then because that’s what gave me the ability to reach out and express myself as an artist to this day. How many people, you know, were stifled from their dream of becoming an artist, or becoming anything? That usually, I really believe, that a lot of people discover that when the kids that, whatever this is supposed to be doing, somehow is either hinted or revealed in their childhood somehow. But a lot of times people just start distracting them, discouraging them, and derailing them, really.

And then at the age of seventeen, you started working for Neal Adams. So for those who don’t know, Neal Adams is one of the most important comic book artists of our time. In the early ‘70s, he really revolutionized the look and feel of Batman. For me, you know, taking this 1960s kind of whimsical Batman and putting him into this more solemn kind of Dark Knight figure that we see today. So how did you get started working with Neal at such a young age?

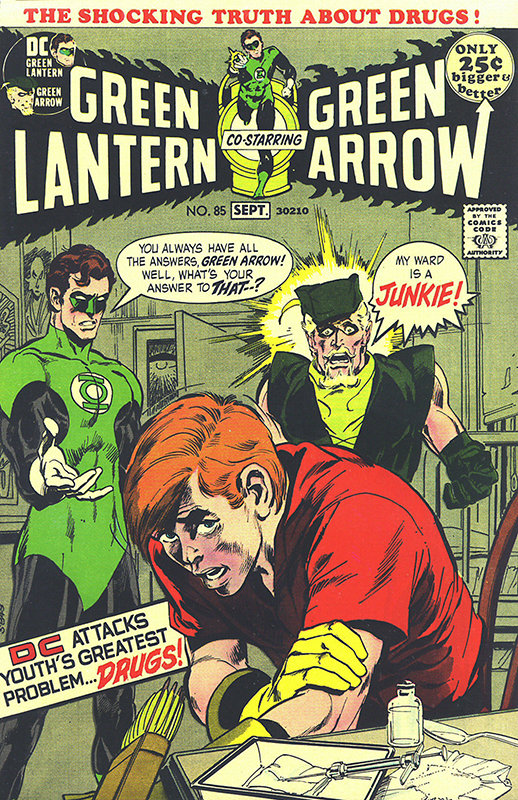

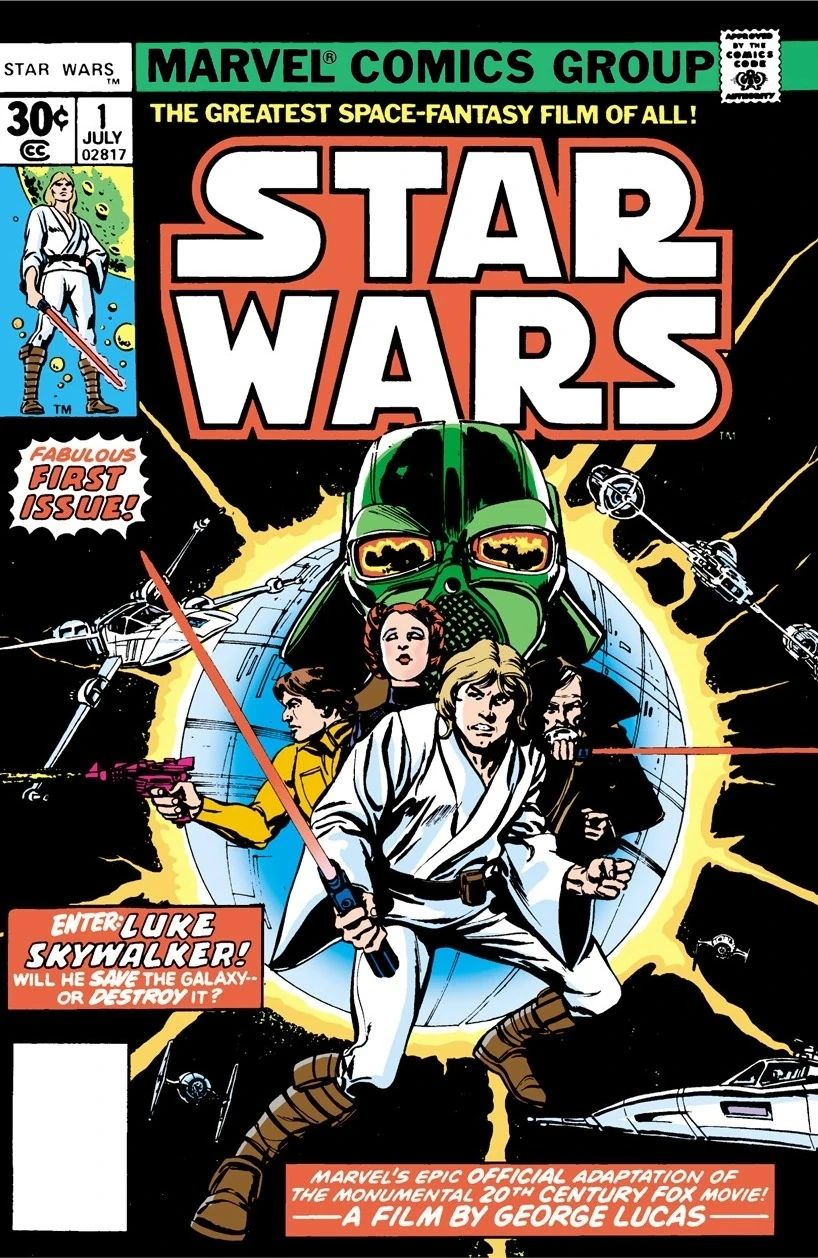

Well, again, I was such a fan forever. You know, when I saw that book that I, you know, that comic book, you see the poster, an image of it back there, it was the Green Lantern and Green Arrow, number 85, it was called “Snowbirds Don’t Fly.” It was the drug issue, very controversial, but very successful. And it really brought attention to this problem, but it wasn’t just that – the artwork in there was just so amazing. I didn’t understand. I was eleven years old and I’d seen many comic books, but I’d never seen anybody put that kind of effort into a comic book. I felt like I was looking at a movie. And, so I started copying his work, you know, trying to become an artist. I didn’t know about Norman Rockwell yet, but I saw Neal Adams and that was like the beginning of… actually Norman Rockwell happens to be Neal Adams’ favorite artist, but, um, mine too.

But, uh, I was copying his work, and trying to learn how to draw like him, and said, “This guy is so good.” So then I’m joking around with my friends in my mom’s basement. You know, my friends would all come there. Really three of us, a few would come, but a few of us were aspiring artists. I would say, you know, “One day Neal Adams is going to ink my pencil drawings.” Which is how comic books are done, you know, one person pencils them. Somebody else inks them, then someone colors them, someone letters them. So I said, “One day Neal Adams is going to ink my pencil drawings.” And of course we laughed. I laughed too. I was, that was when I was thirteen years old. And there was a comic book store called the New York Comic Art Gallery. And I was in high school at this point.

I was sixteen. And I went in there and I couldn’t believe my eyes ‘cause they had a little bit of original art. Now I had never seen original comic book art. It wasn’t Neal – I’d never seen anything before. And they had all these other books. And I was just, I said, “Please, I have to work here!” I was begging the guy to let me work. He said, “Look, I just opened. I cannot afford to pay you anything.” I said, “I don’t care. I’ll work for free. I have to be here.” Eventually I talked him into it, but my mother had told me to get him to pay me something. So he was able to pay me in comic books at first. Then it became a little bit of cash, you know, but I didn’t care because I got to see all these wonderful things I would never have seen before. Anyway, he, one day I went in there and he was such a good… Mark Rindner was his name.

And um, he said, you know, Louis, I don’t want to give you up, but because you’ve been so great, you’ve been working here. My main job is to make sure the kids didn’t steal the comic books. And I sat down and I was hated in high school because the kids were able to kind of sneak every now and then take some books. I was like a hawk watching them to make sure they didn’t take anything. And he loved it. I didn’t care if they didn’t like me. I was working at the New York Comic Art Gallery. And then one day I come in and he says, “You know, Louis, I really love your work. You’re really good. And um, a friend of mine was looking for an assistant and I want to introduce you to him. You know, if you’re interested, he works in the comic book field.”

I said, “Oh my gosh.” I always wanted to find a way to get into it somehow. So I said, “That’d be great. Who is he?” And he said, “Well, his name is Howard Chaykin.” Howard Chaykin is famous for doing the very first Star Wars comic books, among other things. But anyway, I didn’t like Howard Chaykin’s work back then. I love it now. But then it, and it’s like the Picasso. I didn’t understand Picasso’s work back when I was a kid. I thought he couldn’t draw. But with Howard Chaykin, I thought, you know what? Maybe I don’t like his work, but he is in the comic book industry. Maybe he can help me. So when I took the job, he liked me very much. He’s very funny, a really good guy. And I learned a lot of different things, a little bit about business, which I had never touched on.

But then one day I come in and he said, “Hey Louis, you know what? The first Friday of every month, all the comic book artists get together and in New York City and we have a kind of a party. It’s called the First Friday Party. Would you like to come to the next one?” I said, “Are you… yeah, I would love that.” I was going to get to meet all of these other artists. Then he said the magic words, “Oh, by the way, this one’s going to be at Neal Adam’s house.” Now at that point, I kind of got nervous because Neal – he’s great. And his standards are so high, but he’s not very… I won’t say he’s not kind… he’s not soft. When he comes to tell you how he feels about your work, he’s going to tell you straight and coming from him…

So my goodness, anyhow, he says, “Yeah, I want you to come. I want you to bring your sketchpad so Neal can see your work.” I said, “Oh my goodness.” But I was… no, Jesse… I was scared, because if he didn’t like my work, I couldn’t survive that. This is Neal Adams! To me he was God back then. So I went, I brought the work and I said, “Oh my goodness.” I was a very, very shy kid. You can tell I’m very shy, right? But I was a very shy kid and I went in there and… he wasn’t there. He was like in the back room, and I sat there and I saw these other artists like Ralph Reese. And I can’t even remember the names of some of the artists from back then, but I couldn’t believe my eyes.

And I’m holding on to my sketchbooks, and I’m sitting there. I didn’t know what to say. So I’m watching TV, just trying to acclimate myself to the situation. And here he comes. Neal walks in. A big… you know, a big dude. It was him. And he sits down. He’s just looking at me and he goes, and he turns the TV off and he just keeps looking at it. And I’m saying, “Oh my goodness.” Howard Chaykin walks in pretty much shortly after that and Howard makes a beautiful entrance and everything like that. And he said, “Oh, Louis, hey, do you have your sketchbooks?” And he grabbed my sketchbooks and he goes over to Neal, and he’s kind of like on his knees with my sketchbooks on Neil Adams’ lap and he said, “Look at this kid’s artwork. He’s only seventeen years old.” This is when I turned seventeen. “He’s only seventeen years old. Look how he draws better than I do.” And I agreed with that, but I wouldn’t say anything. But it was like so exciting that he was looking at my work. Then Neal starts to turn and he keeps looking at me, and he turns…. almost with every page he looks at me. Then he went backwards, all three sketchbooks. He went forward and backward. And then everybody was looking at me like, “Neal doesn’t do that.”

So then Howard gets up and he says, yeah, Neal, I think this kid is great and he goes to get a drink or something like that. So Neil says, “You know, Louis, you know I like your work very much, and there’s a series of scripts I’ve been sitting on for a long time. I couldn’t find anybody I thought could do it, but I think you can do it. Why don’t you pick up the continuity tomorrow and I’ll get you started on a project.” Jesse, I couldn’t… I said, “Okay, thank you. I have to go now.” And I took my sketchbooks, because I didn’t know what to do myself. I remember it was like 48th or 49th Street and Madison Avenue in New York City. And I’m saying, “Neal Adams just hired me! He looked at my sketchbooks and he hired me!” I can’t… I’m screaming at the top of my lungs.

I didn’t care if the police were going to arrest me. I was so excited. So I went in the next day and he showed me this series of scripts called Tippie Toe Jones. What it was is a little cartoony character who lived in a realistic world, and he saw that I could draw both realistically and cartoony, you know, in a pretty good way. So he started me on the project and that was the beginning. Now, you know, we’re still really good friends. You know, I call him Papa Bear as a matter of fact, but it was from that moment of being seventeen years old, the kind of validation that I would never have expected. I mean, I’m grateful that even though I didn’t like Howard’s work at the time that I took the job, because that’s what led me to this icon that, you know, to this day, I still learn from Neal. And um, to me, he’s one of the greatest comic book writers of all.

What kind of training did you have? I mean, at seventeen, you know, how did you become such a good artist?

Well, at that point I did know about Norman Rockwell because I discovered Norman Rockwell when I was sixteen and the things that I read… see, Mr. Rockwell, again, Norman Rockwell and Jim Henson, the two most generous artists of all time, in my opinion, I’m speaking for myself because when I first saw Jim Henson, you know, he was talking… he did a film called The Muppets on Puppets. And he told all his secrets, even before he was famous. Then Norman Rockwell, he was at the Famous Artists School. And he told everything about how he did his work. He even told people he had a Balopticon – a tracing machine. Now, everybody had one, but he was the only one that came out… And even there’s even a picture of him in that book called Rockwell on Rockwell of him using it. And of course, you still have to know how to draw.

That’s a professional tool like a computer is now. The thing is that I really was just so enamored with what Mr. Rockwell did and the things he said, you know, he would say things like, you know, “You have to do whatever you can to get the right things into your studio.” No matter what you have to give up outside of your studio to get the right things in. These are things that I’d never heard before that artists, I guess the way artists were supposed to speak, but I never heard any of them speak that way. Looking at the Watson-Guptill book and trying to draw the way he did and looking at the way he broke things down, his charcoal drawings, I mean, he would show sketches, even his very preliminary rough drawings. I had never seen anybody do that before. So out of his generosity, I just kept trying to do that.

So I kept getting better and better trying to emulate Norman Rockwell, of course I never even got close and nobody ever will. But I’m glad I got as close as I did because Neal saw that. Again, Norman Rockwell is Neal Adams’s favorite artist. So I was able to bring as much of that as I could. It elevated the… of course I was nowhere near Norman Rockwell, but again, you shoot for the moon, you get halfway there, you’re still way beyond the earth, right? So I was able to get a lot out of Mr. Rockwell’s teachings and it elevated my work to the degree that Neal Adams saw that and hired me at seventeen years old.

That’s great. And did you say that you met Jim Henson?

No. I just missed him. You know, I was in the building two weeks before he passed away and I walked because I was right in front of the townhouse with my son and I’m saying, “Mike, let’s go in there. We can meet Jim Henson.” So I went and I asked, “Is Mr. Henson in?” They said, “Yes, may I have your name?” “Uh, Louis Mitchell.” “I don’t see an appointment.” “Oh no, no. I don’t have an appointment, I just wanted to see if I could meet Mr. Henson.” “Well, I’m sorry, Mr. Mitchell, but you can’t just walk in and meet Jim Henson.” I had to try it, but she… she was a very sweet lady. They had this row of theater seats and a giant painting of the Muppet theater, the audience section. And so we sat there, we took pictures. It was fun. I mean, I didn’t get to meet him.

Then two weeks later on the same day that Sammy Davis, Jr. died, they first announced Sammy Davis, Jr. Now everybody kind of expected Sammy Davis, Jr. to pass away, but no one expected the death of Jim Henson. I literally dropped my coffee cup. I mean, that’s one of those clichés. And I really did, because I wanted to meet him. He meant so much to me. He did so much for me and that was it. But later on, as time went on, I realized, you know what? I wanted to work for the company. And when I finally got the job, I said, “Now that I’m here, I’m going to give my whole heart and soul, the entirety of my heart to continue the work of this man who was so generous. So great.” He considered Sesame Street his most important work, and I’m going to help to… now the thing is, I didn’t know I was going to be promoted into this position.

When I’m Creative Director of Character Design and I’m designing new Muppets, doing all of that kind of work, I didn’t know, I didn’t care, either. I just wanted to know that I was a piece of what he did, what he started. And, you know, he was only at Sesame for, I think about twenty years because he… from 1969 to 1990, so almost twenty-one years. And, um, and that’s about as long as I’ve been at Sesame and now I’m at twenty years, full-time anyway, but it’s more like thirty years because I started freelancing in ‘92, though.

I know Jim Henson is a big idol of mine, too. And, you know, reading his biography, he’s such an inspirational person, it seems like he inspired everyone around him. And I just wondered what… do you still feel his influence at Sesame Street, like the spirit of Jim Henson?

To be honest with you, they tend to not bring him up as much as… you know what I mean, again, not to fault the company, but they are trying to stand on a different ground and they’re trying to establish a different way of pursuing this, but it all came from him. I mean, originally there were not going to be the Muppets on the show, but thank goodness Jon Stone, the original executive producer and head writer, he recognized, “You know, we’re going to need something else.” So he brought Jim in, and because of that Sesame Street now… it’s because of the Muppets that Sesame Street is so… such an international success to this day, fifty… fifty-two now. You know, working on that is people like me, and there are a few other people in there that, you know, “Jim Henson’s everywhere.” I have my favorite picture of Jim Henson, it’s him with Kermit and he’s sitting amongst a bunch of kids and I talk about him everywhere. And it’s in situations like this, it’s why I’m so grateful to you. I’m going to talk about Norman Rockwell and I’m going to talk about Jim Henson and, and, um, wherever I go, whatever I do, I tell people all the time, you know. And again, people love Jim Henson, so they want to hear more about him.

And could you describe a typical day at work for you?

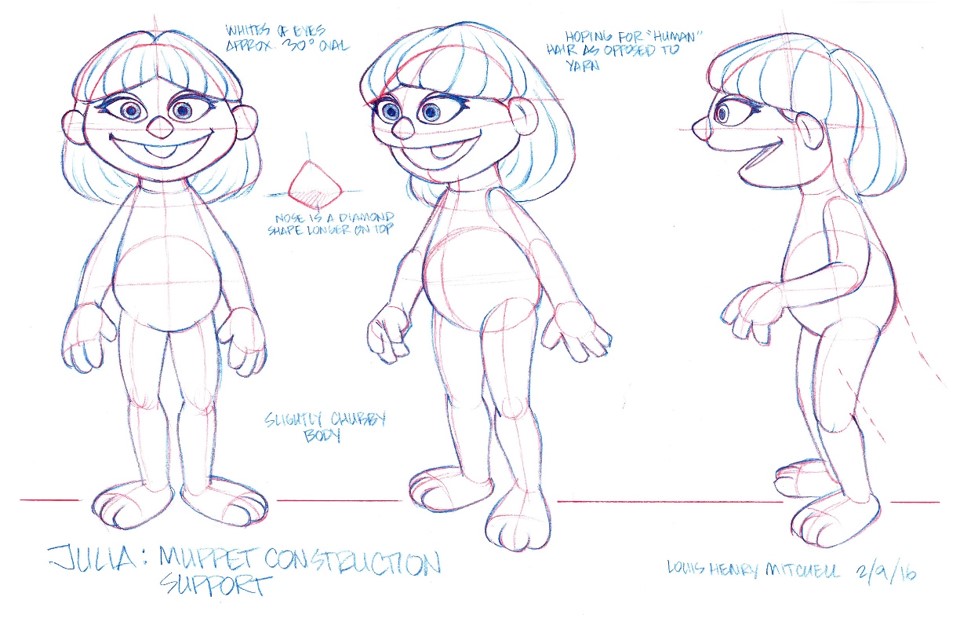

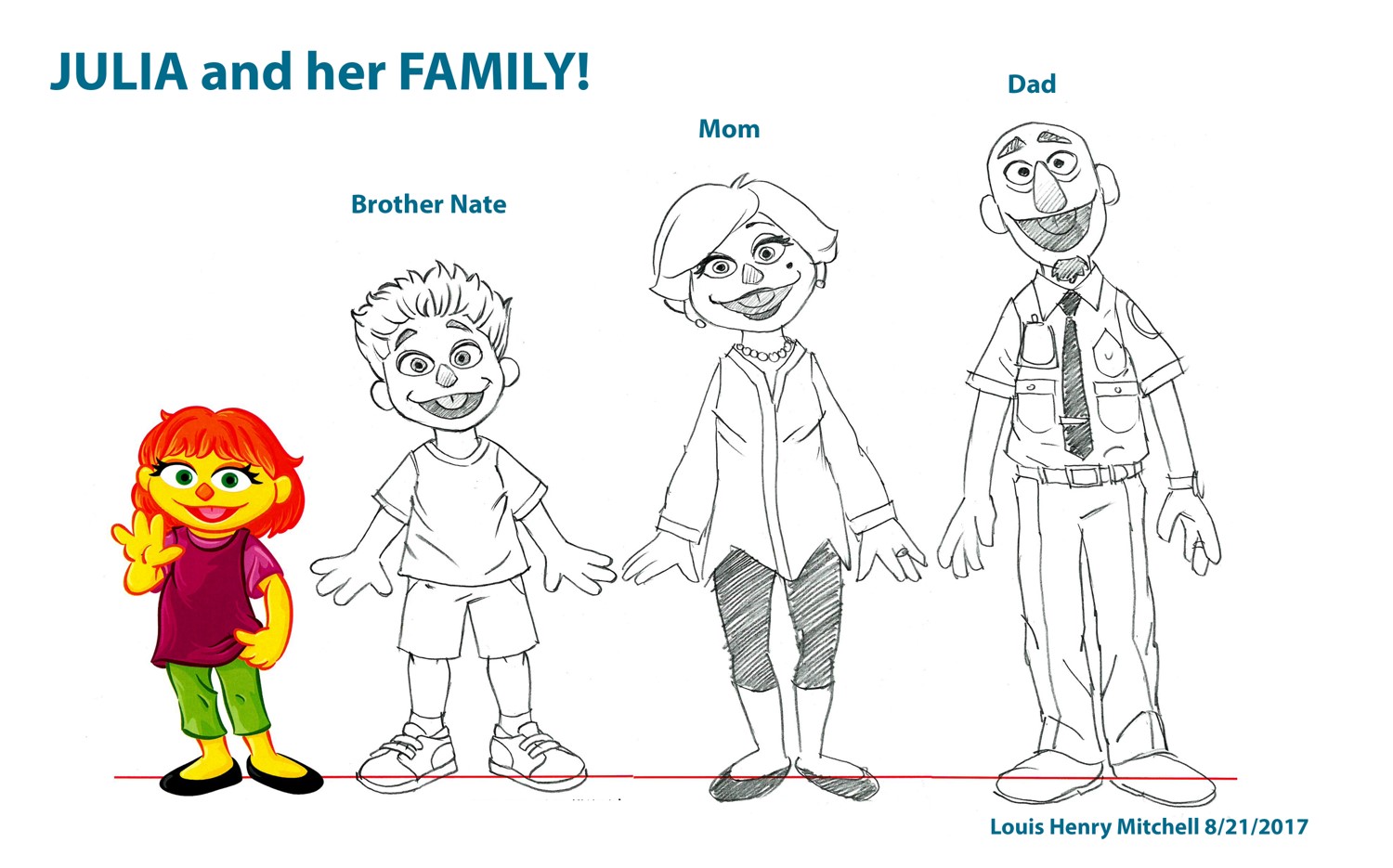

No. There is no such thing as a typical day for… not for me, for a lot of people there really are, but yeah, I never know what it’s going to happen. Now. I have a plan and I have some ideas, but I know usually there’s certain projects I’m working on, on a regular basis, but something will come out of the blue. Like I designed Julia, the autism puppet. I did not see that coming, and you know what? I had already been volunteering at a school for children on the spectrum. I didn’t know at Sesame Street this was something for ten years they had been working on… it’s such a precious and special and sensitive topic that it took them ten years to figure out just how they wanted to do that. I had no idea that was going on, but realizing later on all that work… that volunteer work I did for those kids in their school and at their homes, I was able to bring to this project.

I didn’t see it coming. So I apologize. I can’t answer your question. There is no such thing as a typical day. I can give you the structure that I do approach, though. I’m not supposed to be at work until about 9:30 or so, but I’m usually there… well before all of this has happened right now in the world. I would get there between 7:30, eight o’clock, sometimes earlier. And I go in there and I kind of do a little bit of meditation and just kind of relax. I don’t like to rush. I never rush in the morning. I take my time. I might even choose different ways to get to work in the morning because I do want… I don’t want to miss anything. One of the things I did learn from Norman Rockwell and Jim Henson, but mostly from my son, because I was walking to the school one day and there were these morning glories growing.

And he’d say, “Hey, dad, look.” I said, “Yeah, that’s nice, Mike.” He says, “No, daddy.” He said, “Don’t you miss this?” So because of that, I have embraced this, you know, outlook on life. So I get in nice and early and I can relax and have a cup of coffee, but I go into the music room and I play the piano for about fifteen to twenty minutes. I tend to keep it right around here, but every now and then it gets so good that I’ll play from 7:30, almost up to 9:30. I will not rob the company of official work time, but I have to, at a certain point, I didn’t realize that I was having such a good time. I looked at my watch and it’s like twenty-five after nine. And I said, “Oh my goodness.”

So I finished up my piece to music and I ran back to my desk. Got there right before 9:30. So, um, yeah, so I do have a little bit of a… I wouldn’t call it a ritual. I call it just like a preparation or a cultivation of some kind that I can get my creative juices going. I mean, they’re always going, but to sit down and play the piano for a few minutes, I’ll even sketch, I’ll even draw, sometimes I’ll go online and find some models that I can draw from or anything just to keep… cause again, as artists, I really believe we have to maintain that. Just like a doctor has to practice medicine, an artist has to practice art. Right. Look, you see Norman Rockwell, he went on this trip to Europe and he started doing these sketches of the different parts of Europe. He went to, he went… took art classes, not art classes, but he would do portrait sketches and things like that. These people never stopped learning. And that’s why I adopted that attitude. So yeah, I want to do that. Once 9:30 comes along, though, I don’t know what’s going to happen. And I love that. I love it, love it, love it.

Sesame Street now is on, I think it’s on HBO Max, right? But it’s still… it’s regular HBO. Okay. Yeah. And it still airs on PBS, and I guess how important is it to you that Sesame Street is available on public television so that anyone can watch it?

Yeah, no, absolutely. It’s vital because, um, a lot of people don’t have access to cable or HBO. Now the thing is that HBO really did a great thing for us. They funded the production of a lot more episodes that we’ve been doing for awhile. Now, the thing is they get to air those episodes first. I think eight months, eight or nine months, I guess, eight months later, they air on PBS. So the thing is that, I mean, as long as they get to air, you know, that’s the main thing. So it’s important that kids have access to that show. The other thing is that kids also have access to the books. There’s a lot of books, Sesame Street books and that’s another thing I also do, I art direct all the children’s books. They spend more time with those books than they do with the television shows, so I pour my heart and soul into that, too. So as long as kids have access to Sesame Street and they don’t have to rely on cable or even digital content, which I’m glad we’re doing that, you can find this everywhere, but what about the people that don’t have internet access and a lot of people don’t. I mentioned that a lot of people don’t have cable, but PBS is right there to make sure we always get our feed on Sesame Street.

That’s great. Thank you so much, Louis. And thank you for all of all you do to bring so much joy and magic to children and adults alike. You’re doing such a great job.

Thank you. It’s a privilege and honor, and I am grateful. So thank you for this opportunity. It’s really great.

Well for more information, check out Sesamestreet.org for games, videos, and art projects, and our own websites. nrm.org, illustrationhistory.org, and visit the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies at rockwellhyphencenter.org. And don’t forget to subscribe for the latest content and, that’s it, Louis. Thank you so much.

VIDEO

IMAGE GALLERY

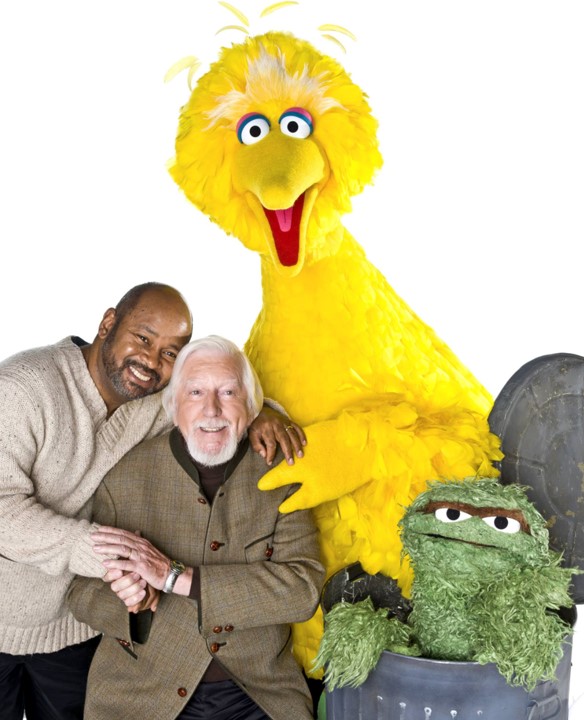

Louis Mitchell, Carroll Spinney, Big Bird, and Oscar the Grouch, n.d.

All images from Sesame Street, © 2021 Sesame Workshop

Frank Oz and Louis Mitchell, n.d.

Louis Mitchell and Snuffleupagus, n.d.

All images from Sesame Street, © 2021 Sesame Workshop

Jesse Kowalski, Louis Mitchell and Cookie Monster, 2019

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

Freedom From Want, 1943.

Illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March, 6, 1943.

From the collection of Norman Rockwell Museum.

© 1943 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN. All rights reserved.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

Triple Self-Portrait, 1959.

Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, February 13, 1960.

Oil on canvas

Norman Rockwell Art Collection Trust, Norman Rockwell Art Collection Trust, NRACT.1973.019

© 1960 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN. All rights reserved.

Louis Henry Mitchell, Jim Henson and Kermit the Frog, n.d.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March 17, 1934

Tearsheet

Norman Rockwell Art Collection

© 1934 SEPS: Licensed by Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN. All rights reserved.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

The Problem We All Live With, 1963.

Story illustration for Look, January 14, 1964

From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

Licensed by Norman Rockwell Licensing Company, Niles, IL

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

New Kids in the Neighborhood, 1967.

Story illustration for Look, May 16, 1967

From the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum

Licensed by Norman Rockwell Licensing Company, Niles, IL

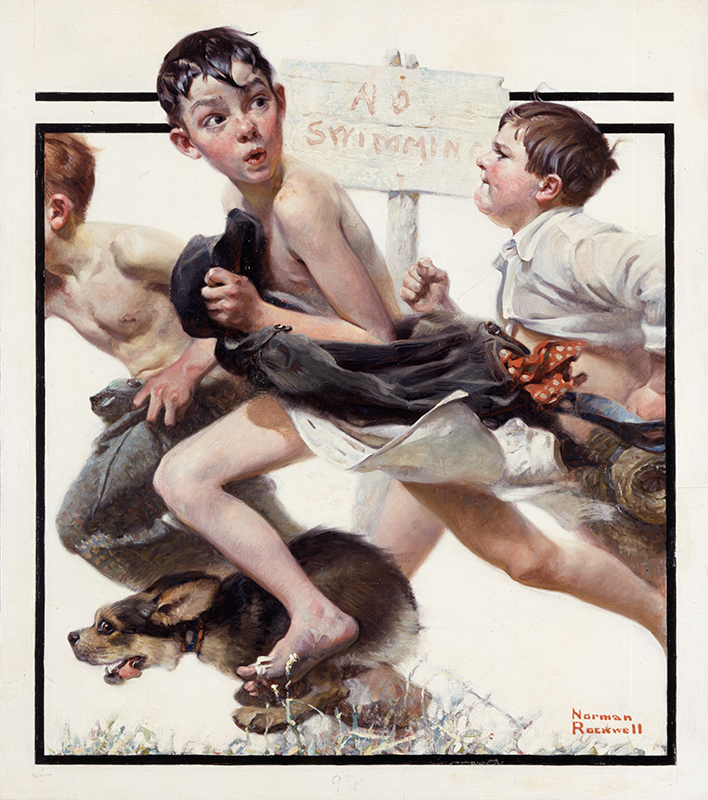

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

No Swimming, 1921.

Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, June 4, 1921

Oil on canvas

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, Norman Rockwell Art Collection Trust, NRACT.1973.15

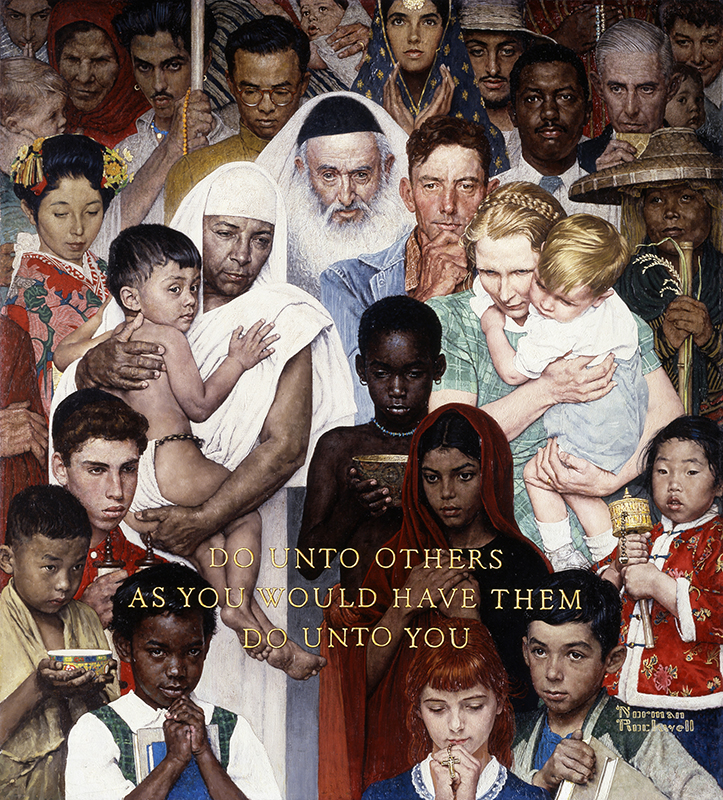

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

Golden Rule, 1961.

Oil on canvas, 44 ½” x 39 ½”.

Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, April 1, 1961.

Norman Rockwell Museum Collections.

©1961 SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN

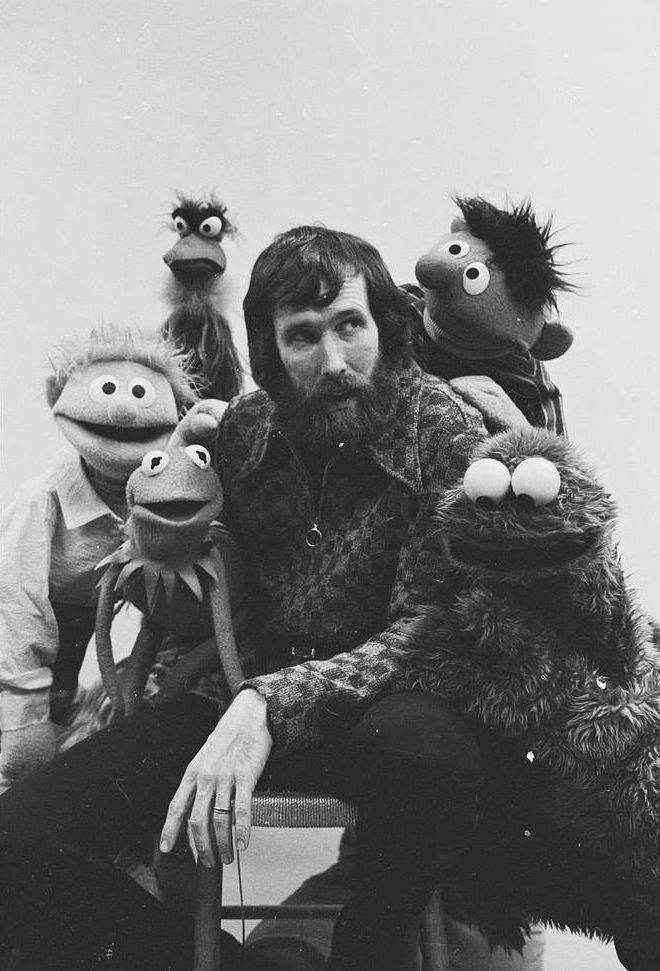

Bernard Gotfryd, Jim Henson Surrounded by his Muppets, 1971, Courtesy Library of Congress

14 Louis Mitchell at age six

Ed Sullivan, Kermit the Frog, and Jim Henson, n.d.

Louis Henry Mitchell, Elmo with Heart, n.d.

Louis Henry Mitchell, Cookie Monster, n.d.

Louis Henry Mitchell, Cookie Monster, n.d.

Louis Henry Mitchell, Grover, n.d.

Louis Mitchell with the Muppets, n.d.

All images from Sesame Street, © 2021 Sesame Workshop

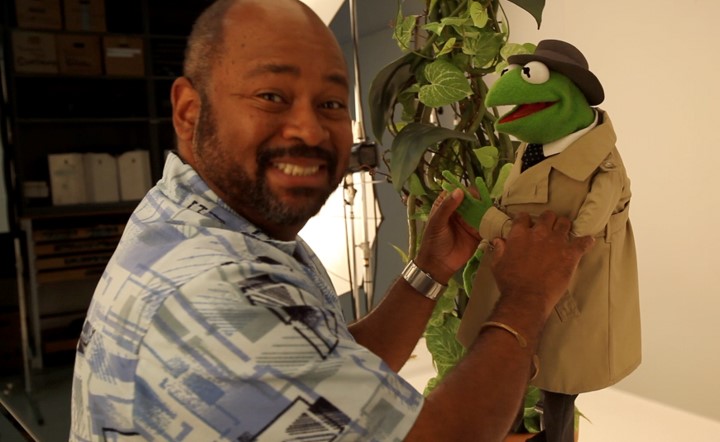

Louis Mitchell with Kermit the Frog, n.d.

All images from Sesame Street, © 2021 Sesame Workshop

Photograph of Neal Adams, n.d.

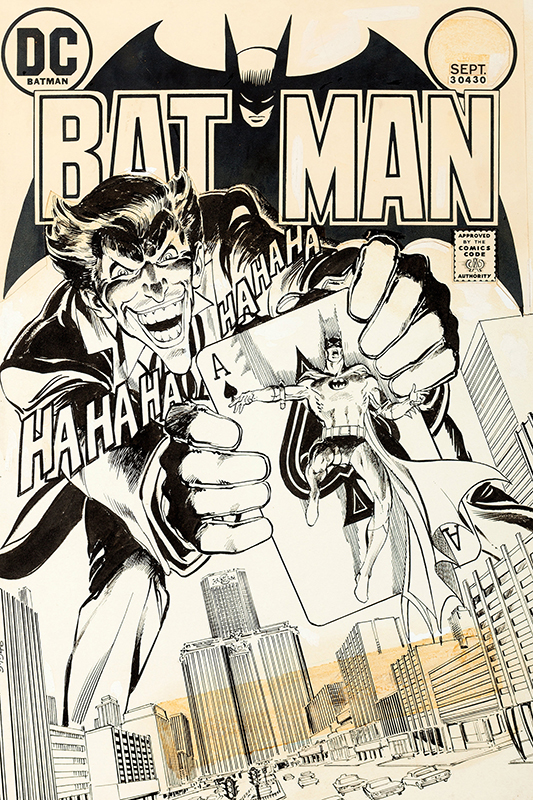

Neal Adams, Cover of Batman, No. 251, September 1973

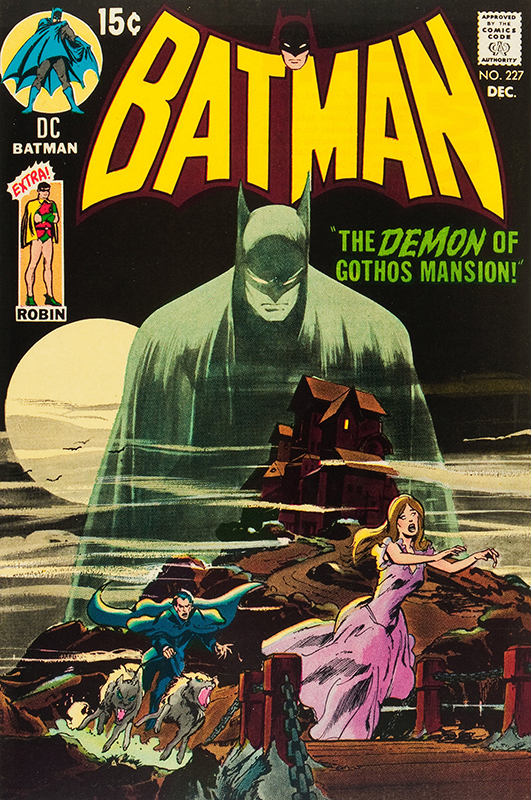

Neal Adams, Cover of Batman, No. 227, December 1970

Neal Adams, Cover of Green Lantern, No. 85, August 1971

Howard Chaykin, Cover of Star Wars, No. 1, July 1977

Louis Henry Mitchell, Concept art for Julia, 2016

All images from Sesame Street, © 2021 Sesame Workshop

Louis Henry Mitchell, Concept art for Julia and her family, 2017

All images from Sesame Street, © 2021 Sesame Workshop

Marybeth Nelson, Cover for We’re Amazing, 1, 2, 3!

All images from Sesame Street, © 2021 Sesame Workshop

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration explores fantasy archetypes from the Middle Ages to today. The exhibition will present the immutable concepts of mythology, fairy tales, fables, good versus evil, and heroes and villains through paintings, etchings, drawings, and digital art created by artists from long ago to illustrators working today.

The exhibition Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration is organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, and will be on view here from June 12 through October 31, 2021.