Louis Glackens (1866–1933)

Louis Glackens (1866–1933)

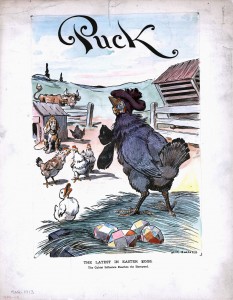

The Latest in Easter Eggs. The Cubist Influence Reaches the Barnyard, 1913

Cover illustration for Puck (March 19, 1913)

Lithograph and watercolor on illustration board

DelawareArt Museum, Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978

On February 17, 1913, the International Exhibition of Modern Art opened at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City. The exhibition, which would become known as the Armory Show, was organized by a group of American artists and featured over 1,200 works of art from Europe and the United States. The event introduced European modern artists—including Picasso, Brancusi, Matisse, and Duchamp—to a broad American audience. The show attracted enormous attention from the popular press, as major newspapers and general interest magazines joined art journals in reviewing and debating the art on view. Avant-garde artistic movements, like cubism, fauvism, and futurism, garnered a great deal of the mainstream media attention. In 1913, some American artists were already experimenting with these styles, and examples of Cubism and Post-Impressionism had been displayed at Alfred Stieglitz’s Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue—but the Armory Show vastly expanded the conversation. Due in part to sensational press coverage, the exhibition attracted an audience beyond those that usually attended exhibitions of art; approximately 88,000 visitors attended the venue in New York.

Indicative of the public interest in the Armory Show, American humorists joined in the commentary. Louis M. Glackens’ timely cover for the weekly humor magazine, Puck (seen above), with its cubist Easter eggs, testifies to the degree to which the Armory Show expanded the discussion of contemporary art in America. Although its illustrators occasionally parodied art exhibitions (and the people who attended them), Puck was a general interest humor magazine that mainly addressed political and social issues. And, like the organizers of the Armory Show, Puck targeted a national audience. As the cartoon’s subtitle—“The Cubist Influence Reaches the Barnyard”—implies, talk of the Armory Show spread beyond New York and the show itself traveled. A selection of works from the exhibition went on the road to the Art Institute of Chicago and, later, Boston. When this issue of Puck appeared on the newsstands, the avant-garde art was moving through the Midwest. The crates arrived in Chicago’s Union Station on March 21, 1913.

For the cover of Puck, Glackens inserted an arcane, urbane artistic movement into a pastoral scene, setting up contrasts between nature and art, tradition and modernity, garden and machine. Four angular eggs are presented by a chicken, wearing the floppy cap and oversized bow tie that signaled artistic identity in turn-of-the-century cartoons. Proud of her progeny, the artist-chicken stands atop her nest with beak in the air, while the farm animals look on, incredulous. Other chickens—brown and white and altogether more chicken-like—cluck to each other, while a duck quacks at her and a cow stares wide-eyed. With her eyes closed, the artist-chicken appears a bit defensive; she does not seem surprised by the reaction her eggs receive. The chicken’s dark, floppy accessories—standard in cartoons by the 1890s and a cliché by 1913—contrast with the smooth, mechanical, and colorful eggs. The proud hen looks like an artist from one era introducing the next, and she may represent the artists behind the Armory Show. The primary organizers of the exhibition—Walter Pach, Walt Kuhn, and Arthur B. Davies—were not working in the most radical styles presented in the exhibition, but they were enthusiastic about introducing innovative European art to the United States. The reactions of the various animals reflect the variety of responses elicited among artists, critics, and the general public, by the Armory Show.

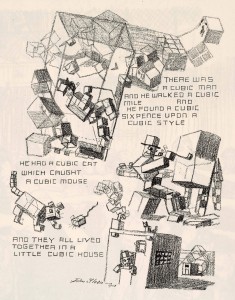

The cartoonist, Louis M. Glackens, may have been better prepared than many to make fun of modern art. His younger brother, the painter William Glackens, was involved in organizing the exhibition, and in 1912 had purchased the first group of European modern paintings—including post-impressionist works by Cézanne, Picasso, and Renoir—for the collection of Albert Barnes. The Glackens brothers were close and both lived in New York, where Louis worked at Puck for two decades. Also friendly with painters and collectors in his brother’s circle, Louis M. Glackens could have participated in some interesting conversations about contemporary art. Neither William Glackens, nor his high-school friend Barnes, really warmed to cubism, which provided some of the best material for parodists of the Armory Show. John Sloan, who knew both William and Louis since high school in Philadelphia, responded to the cubist art at the exhibition with a cartoon of his own, which appeared in the socialist journal, The Masses (seen below). Like Louis M. Glackens’, Sloan’s humor is clever and nonjudgmental; both testify to the broad reaction among American artists, illustrators, and their diverse audiences, to the art presented in the Armory Show.

John Sloan (1871–1951)

John Sloan (1871–1951)

A Slight Attack of Third Dimentia Brought on by Excessive Study of the Much-talked of Cubist Art in the International Exhibition at New York, 1913

Printed illustration from The Masses (April 1913)

Delaware Art Museum, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives

These cartoons were part of a long standing tradition of responding to new art with cartoon and caricature—a tradition that American artists imported from France in the 1870s. In 1878, Puck introduced the practice, printing a page of caricatures of works of art from the first exhibition of the Society of American Artists (see below). Drawn by the magazine’s founder Joseph Keppler, the caricatures, like Glackens’ and Sloan’s cartoons, made light of innovative art being shown in highly publicized exhibition: the Society had been founded in protest to the conservatism of the National Academy of Design, and its inaugural exhibition was highly anticipated and heavily reviewed in the press. Keppler spoofed the most talked-about works in the 1878 exhibition, and twenty-five years later, Glackens turned his gaze on cubism, which was among the most discussed and derided styles of art at the Armory Show.

Joseph Keppler (1838–1894)

Back cover illustration from Puck (March 27, 1878)

Printed illustration

The Literature Department, Free Library of Philadelphia

The Glackens cartoon at the DelawareArt Museum is not the printed cover, but a color study for the final design. Having produced a lithograph based on Glackens’s initial drawing, the publisher sent the cartoonist this double-sided print on illustration board. (I assume it was double-sided in case the artist made a mistake.) The artist then painted it in watercolor and returned the proof to the press room. A stamp on the back instructed Glackens to return it by 11 a.m. on March 6, 1913. Considering its practical function, it is surprising that this study for a historic cartoon survived. It was purchased by John Sloan’s widow Helen Farr Sloan, with a group of Glackens’ drawings for Puck, and given to the Delaware Art Museum in 1978. It has rarely been shown, and I was delighted to discover it in the collection last month—the day before the Centennial of the opening of the Armory Show.

The hundredth anniversary of the Armory Show has inspired major exhibitions and publications from the Montclair Art Museum and the New-York Historical Society. To learn more about the Armory Show and critical responses to it, see the amazing timeline assembled by Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art: https://armoryshow.si.edu/.

March 21, 2013

By Dr. Heather Campbell Coyle, Curator of American Art at the Delaware Art Museum