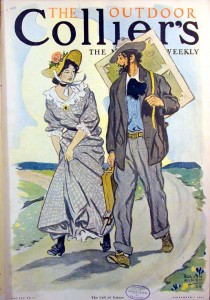

Rollin Kirby (1875-1952)|The Call of Nature, 1908|Cover illustration for Collier’s Weekly (September 5, 1908)

Early in the fall of 1908, Collier’s Weekly’s cover showed a man and woman walking together along a foot path. Floating in the blue and white in the sky, above the masthead are the words in caps and red ink, “The Outdoor.” Read together with the weekly’s title, the appended title tells us that this issue is about the out doors. The couple walking along the path of the cover image, are meant to reinforce the purpose of this issue. But this couple is both more and less than they seem. While they walk together along the same path, they represent two different life styles.

The attractive young lady seems nicely put-together. Her dress collar and cuffs are edged in ruffles. She wears a decorative pin attached where the collar comes together along the neckline. In an attempt to keep her hem clean, the young lady lifts her skirt as she walks along, thereby showing a bit of her black stocking-clad ankles. Her simple straw sun bonnet echoes a type sometimes seen adorning the heads of some of Winslow Homer’s images of pretty young ladies in his illustrations and paintings from 30 years before. With its wide brim and shallow (to non-existent) crown, this bonnet was simple enough to have been home-made. Similarly the simple outfit she wears could have been made by hand.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910)|On The Beach--Two Are Company, Three are None, 1872|Illustration for Harper's Weekly (August 17, 1872)

The man walking and talking with her appears rather slovenly by comparison. His hair and beard are unkempt. His pant legs are not cuffed but rolled-up revealing his white socks. His jacket is loose and unstructured. Indeed around the turn-of-the-century, most American men (except for the wealthy) began to purchase mass-produced suits at department stores and clothing emporiums. The baggy ready to wear style of jacket was called a sack jacket, meaning that its body was loosely shaped and looked more like a bag than a fitted jacket popular in the past and was made in standard sizes. The man’s shirt collar may be white, but his shirt is blue. Blue and gray colored shirts were more often worn by working men, and usually their collar color matched the shirt, hence the term, a blue-collar worker. Most unusual is the soft floppy bow tie he wears under his collar. A gentleman would have worn a more formal cravat or bow tie around his stiff collar. The floppy bow tie style was solely worn by artistic types, like Frank Lloyd Wright and Elbert Hubbard as seen in the photos below. The man’s scruffy hat is tipped rakishly over his forehead.

Photo of Elbert Hubbard (1856-1915) The artist, that we can now identify him to be, carries a collapsible easel and paint box bound together in his right hand. Suspended from a strap hung over his back and held in his left hand is the painter’s stretched canvas. In the 19th century it became commonplace for artists who specialized in landscapes to take their equipment with them and work out of doors. The illustrator Howard Pyle created an oil sketch of just such an event, picturing himself creating a similar sketch of the land around Fort Ticonderoga; the spirit of Ethan Allen looks on over his shoulder. Howard Pyle (1853-1911)|Untitled vignette, 1896|Delaware Art Museum, gift of Marion Mahony Manning in memory of Mary Poole Mahony, 1991-165

Around the same time as the Collier’s cover, the American realist author William Dean Howells’ novel, The Landlord at Lion’s Head, was published. The observer and primary teller of the tale is a young artist on a walking and painting tour in the New Hampshire mountains. Howells describes the local folk’s first sight of the landscape artist early in the story. “He pointed down the road at the figure of a man briskly ascending the lane toward the house, with a pack on his back and some strange appendages dangling from it.”* Those appendages would have been a portable easel, a color box, and maybe even an umbrella.

Rollin Kirby’s cover illustration for Collier’s illustrates a conventional member of society, the woman, and an unconventional one, the artist, walking along the same path but with probably different goals for their activities. ** Each of them is enjoying their jaunt and apparent interaction. Their activity invites us all to find our own path as we explore the outdoors. Enjoy your summer.

I do not intend the title of this piece to refer to elimination functions.

* William Dean Howells, The Landlord at Lion’s Head (New York: Harper Brothers, 1908): 10.

** This pastoral scene is not the usual type of illustration work for which Rollin Kirby is best remembered. Later in the 1920s Kirby would transform a mid-19th century cartoon character into the tall black-coated seedy narrow-minded persona, “Mr. Dry.” The original gentleman prohibition canvasser was created earlier by cartoonist Joseph Keppler. During Prohibition at least seven other political cartoonists used their versions of Mr. Dry to help bring down the Volstead Act. After Prohibition was over, Mr. Dry was credited with having “. . . laugh

June 17, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum