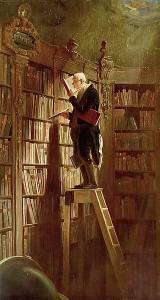

Carl Spitzweg (1808-1885)

The Bookworm, 1852

Oil on canvas

Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt, Germany

This article forms a direct response to Daniel S. Palmer’s recent consideration of Romanticist influence on Norman Rockwell.* In his work, Palmer noted the artistic technique of the Rückenfigur, a term which is remarkably appropriate to Rockwell’s homage to Carl Spitzweg’s painting The Bookworm (Der Bücherwurm, 1852).** As Palmer noted, Rockwell was undoubtedly aware of Spitzweg, given that he had no less than three books on the German artist in his own library. This is probably why Rockwell translated The Bookworm from the nineteenth century to 1920s America in his own illustration (as seen below).

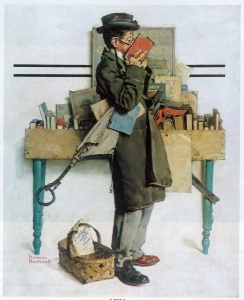

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

The Bookworm, 1926

Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post (August 14, 1926)

Oil on canvas

Private Collection

When stood alongside one another, it is clear that The Bookworm of 1926 derives from Spitzweg’s painting in title, structure, form and topic. Yet his figure was both literally and figuratively the reverse––the back or Rücken as it were––of that depicted by Spitzweg. The similarities of composition are immediately obvious, and it appears clear that this illustration was a form of tribute to Spitzweg. The leaning figures absorbed in their reading, texts tucked underarm, feet slightly spread, are book-ends across roughly seventy-five years of art.

It is apparent that Rockwell copied the stance of the original Bookworm (described by Jochen Becker as “the appearance of a question mark”) and maintained the same sense of slight imbalance.*** The German Bookworm, lost in a study of ‘Metaphysics,’ is perched atop an enormous ladder and has to bend his knees to hold yet another book in addition to those he holds in his hands and under his arm. Rockwell’s figure adopts the same pose, also bending at the knees––though apparently more to balance the large umbrella that he carries. His particular interest (as repeatedly proclaimed on the table behind) is ‘Art’: like Spitzweg’s gently ironic ‘Metaphysics,’ a rather large topic.

But this is mostly a reversed image. The Bookworm of Spitzweg is a solid German burgher, dressed in a coat and eminently respectable from his collar to his knee-breeches (aside from his large trailing handkerchief). This fitted very much with the ‘bourgeois’ aspect of Spitzweg’s work, what Novotny refers to as “German Biedermeier Romanticism”.**** The detail of the handkerchief trailing behind Spitzweg’s Bookworm further humanises the subject, and is rather evocative as a dash of white against the deep black of the frock-coat. In an otherwise fairly neat if “rather unfashionable” outfit it speaks of forgetfulness. Like much of Spitzweg’s work (witness, for instance, The Poor Poet) this was intended as a gently humorous caricature.*****

Rockwell’s Bookworm is far more eccentric but the illustration is just as gentle in its humour. With his long coat, rather battered hat and odd shoes (one black, one brown), this Bookworm’s coat has been buttoned incorrectly, and he trails what appears to be the tie for his umbrella in near exact symmetry to Spitzweg’s handkerchief. Rockwell has also depicted a far more absentminded reader. The basket at his feet contains a note written out for chores that are ignored as he browses. He is even more oblivious to everyday matters (like clothing) than Spitzweg’s character, though arguably the latter is more ‘lost’ than the former, existing in a realm that seems to be made entirely of books.

The setting, too, has taken an interesting turn. From Sptizweg’s action inside a large library, in Rockwell we move outdoors to a rather random arrangement on a bookstall. Rockwell provides a ramshackle setting; elegant and carved bookshelves are replaced by a roughly built table that is propped up at one corner. One is genteel, the other is perhaps shabbily genteel. Where Spitzweg’s Bookworm appears to depict privilege, Rockwell portrays the everyday.****** What this illustrates is that Norman Rockwell was not only self-consciously basing his illustration on the Romanticist movement, but that he was appropriating it in his own unique way, and adjusting it to reflect his perception of American society. Much had changed from the German Bookworm to his American cousin but one thing had not. Despite the elevated position of one and the grounded position of the other, both men have their heads in the clouds.

* Daniel S. Palmer, “Norman Rockwell and the Rückenfigur,” https://www.rockwell-center.org/exploring-illustration/norman-rockwell-and-the-ruckenfigur/ See also Joyce K. Schiller, “Appropriating Art,” https://www.rockwell-center.org/exploring-illustration/appropriating-art/

** See Alois Elsen, Carl Spitzweg (Vienna: Anton Schroll, 1952), 80-81, plates 16 and 17. On this image, see especially: Jochen Becker, “Librarians, Life and Ladders: Carl Spitzweg and Others,” trans. Elborg Forster, Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation, Vol.13, No.3-4 (March 1998): 309-330.

*** Becker, “Carl Spitzweg,” 311.

**** See the profile by Mary Benderson, “Carl Spitzweg: A Unique Chronicler of German Bourgeois Life,” Apollo: The International Magazine of Art & Antiques Vol.103 (January 1976): 48-52; Fritz Novotny, Painting and Sculpture in Europe, 1780-1880 (New York: Penguin, 1980), 227-237. Biedermeier refers to a form of middle-class German sensibility and style of the nineteenth century.

***** Becker, “Carl Spitzweg,” 311; see Der arme Poet (1839): Elsen, Carl Spitzweg, plate 6; Novotny, Painting and Sculpture in Europe, 228.

****** One is even tempted to suggest that Rockwell had combined two images by Spitzweg in one, the shabby prop-table bookstall of the Antiquar (second-hand bookseller) from 1855 and The Bookworm: see figs. 2 and 3 in Becker, “Carl Spitzweg,” 312-13.

March 7, 2013

By Dr Samuel Koehne, Alfred Deakin Research Institute, Deakin University, Australia