Worth Brehm (1883-1928)|Telling Stories, n.d.|Illustration for “Nowhere In Particular” in American Magazine|Charcoal, pencil and whiting on paper|Norman Rockwell Museum, gift of The Horvath Collection, NRM.2008.01

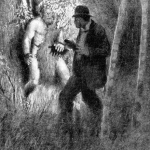

Worth Brehm’s Telling Stories illustrates what an illustration is. To illustrate is to illuminate, like a spelunker does a cave, as the literary historian J. Hillis Miller notes.

In Brehm’s charcoal drawing of one boy telling a story to two others, the lantern at the center refers not only to the story-telling boy’s powers of illumination but those of the illustrator himself. Both bring worlds to light through a story-telling art. Like other illustrators from the time, such as Harvey Dunn in his 1910 illustration for a Jack London story, He pressed the button . . . (fig. 2), Brehm comments on illustration’s own powers of revelation.

Figure 2: Harvey Dunn|He pressed the button . . ., 1910|Illustration for a Jack London story

Brehm’s drawing is about illustration in other ways as well. The story-teller and his two listeners are all on the same level. Story-telling and illustration are both democratic arts, the drawing implies. The head of the story-teller is on the same horizontal line as that of the two speakers. The boys look to be about the same age. Each wears a cap with the bill turned backwards, and each seems to wear the same general type of clothing such as collared shirts. Perhaps in the story the drawing illustrates (unknown at this time), they all belong to the same club. Making and enjoying story-telling illustration are conceived as affairs of equals, secret societies set aside for the pleasure of communal rituals.

Story-telling is literally a child’s business (and here especially a boy’s concern). The capacity to tell a story—and to be absorbed by it—is a child’s natural gift, according to Brehm. The illustrator himself can immerse himself in a story with the spontaneous, unselfconscious concentration we see in the three boys. The story-telling boy’s inwardness—his crossed legs, his closed right fist, his tie tucked into his shirt, and (what looks to be) his inward gaze, as if at the events and people he tells of—all suggest Brehm’s own powers to be absorbed by what he portrays. The listening boys, no less absorbed, seem to follow his every word. The lantern, just below the story-teller’s raised finger, is the icon of his narrative art, and we can readily imagine that he is the one who has brought them to this space by holding that lantern by its semicircular handle. But the X pattern on that same lantern suggests that, when it comes to stories, the energies of the listeners as much as the teller cross, and re-cross, the tight space of a shared imaginary world. An illustrator’s viewers, no less than a story’s listeners, bring their own energies to a scene.

Story-telling, it follows, is cast as a primitive art. Brehm’s illustration evokes images of prehistoric or so-called primitive peoples perched around their campfire telling stories or singing songs of the darkened world, such as the Apaches of Frederic Remington’s 1908 Apache Medicine Song (fig. 3). In the social evolutionary theories of the early 20th century, children as much as racial others were said to be closer to the earth. Surely it matters that the boys in Brehm’s illustration are sitting on the floor. Had they been standing up, the story-telling scene would have a very different feeling. To tell a story—and to make a narrative picture about story-telling—are cast as anti-modern, as primitive, as a childish domain of special, naïve absorption. Norman Rockwell’s mesmerized, shocked, and incredulous little boys belong in this tradition of illustration.

Figure 3: Frederick S. Remington|Apache Medicine Song, 1908

Way back in the art-historical and cultural past of Brehm’s image is religion. With its chiaroscuro, it is a distant vestige of Catholic religious painting, notably works such as Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus (fig. 4). Just as the resurrected Jesus suddenly revealed his true identity to the disciples he’d been traveling with (they had thought him a stranger), so the white-shirted boy in Brehm’s drawing makes a revelation by a light that comes from both before him and, it seems, within him. Brehm’s illustration is not thereby religious itself, but it derives from scenes of religious epiphany to portray what it is to convey a story to a rapt and amazed audience of loyal devotees.

Figure 4: Caravaggio|Supper at Emmaus

October 8, 2009

By Dr. Alexander Nemerov, Department of the History of Art, Yale University