Frederic Remington (1861-1909)

Frederic Remington (1861-1909)

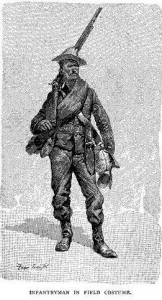

Infantryman in Field Costume (The Infantryman), 1890

Story illustration for “General Crook in the Indian Country” by John G. Bourke, Captain, 3rd Cavalry, U. S. A., in Century Magazine v. 41, no. 5 (March 1891)

watercolor and gouache on illustration board

Collection of the New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, CT, Harriet Russell Stanley Fund (1952.16)*

Infantryman in Field Costume is an example of the artist’s observant eye and talent for narrative art. It was made as one of twelve illustrations to accompany an article by Captain John G. Bourke of the 3rd Cavalry, U. S. A., published in Century Magazine. This illustration not only reflects Remington’s long-standing interest in the military,** but his comprehensive knowledge of its culture. His knowledge and familiarity with the mores of military life came about as a result of his being “embedded” with the army on many of its campaigns during the Indian wars of the late nineteenth century. “No man,” he wrote, “earns his wages half so hard as the soldier doing campaign work on the Southwestern frontier.”*** By the time Infantryman in Field Costume was published, Remington had consolidated his reputation as an illustrator of life in the West, particularly U.S. Army life. In that year, in addition to Infantryman in Field Costume, Century Magazine published another 18 of his illustrations, Harper’s Monthly, 36 and Harper’s Weekly, 119 – all about the West and all in that single year. He became an enormous success in a very short time.

Like such artists and writers who depicted the West as Owen Wister, Theodore Roosevelt (both of whom became friends and whose books he illustrated), Charles Schreyvogel, Frank Schoonover, N.C. Wyeth and Mary Hallock Foote, Remington was an Easterner. He was born and raised in Canton and Ogdensburg, New York. His formal art training was minimal: two years at the Yale School of Fine Arts beginning in 1878, under John Henry Niemeyer and later in 1886, a brief stint at the Art Students League of New York.

John Henry Niemeyer (1839–1932)

Professor Du Bois, n. d.

Watercolor sketch

Yale University Art Gallery, bequest of John Ireland Howe Downes, B.F.A. 1898, 1934.32

As a painter / illustrator of Western and military subjects, his work is known for its high degree of realism and meticulous detail. The visual depiction of this foot soldier, from his campaign hat and bedroll to his well-worn boots, along with his equipment, or what Remington termed his “service trim,” seems to be veracity itself. As a recorder of military life Remington is part of a strong Anglo-European tradition, in particular the work of the nineteenth century French artists Adolph de Neuville and Édouard Detaille by whom he was influenced. [See an example of Detaille’s work below.] He had reproductions of their work in his studio files. Detaille has been called the semi-official artist of the French army. Similarly Frederic Remington could also be considered the semi-official artist of the American Frontier army.

Édouard Detaille (1848–1912)

Cuirassier, 1872

Watercolor on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Maria De Witt Jesup, 1915, 15.30.27

However, Remington was also a writer and he affectionately describes the infantryman of his day as follows: “ The infantryman in his brown canvas clothes has more the look of a navvy than the smart military character, and frequently a toe has worked through a shoe. . . . The villainous knives issued to the “doughboys” complete a sinister aspect. . . still, they have their use in the domestic affairs of the soldier while serving in place of the discarded bayonet. . . . A big tin cup flaps from its fastenings on the haversack.” The haversack, which replaced the backpack, probably contained his mess kit, shaving gear and perhaps a minimal change of clothing. The ammunition belt replaced the ammunition box and the rifle was probably a breech-loading, single shot Springfield. Remington continues: “and the ‘set ‘of the pantaloons, tucked and wrinkled in the service boots, is far from fashionable.”**** The use of the word discarded implies the continuing problem faced by the War Department in arming and clothing the Nation’s Frontier Forces. Yet in the case of the image of Infantryman in Field Costume, Remington transcends description, going beyond realism and his meticulous detail to grasp character. Through his taut and wiry line he conveys his admiration for the soldier’s dignity, pride and sense of professionalism.

* This illustration is inscribed, “U.S. Infantryman in service trim with compliments to J. S. Hartley.” Jonathan Scott Hartley (1845-1912) was an American sculptor; a student of Erastus Dow Palmer; and the son-in-law of the painter George Inness. His most famous work is called The Whirlwind and was cast in 1896. Hartley and Remington were friends.

** Remington’s father had organized a volunteer cavalry regiment during the Civil War and Remington had been a student at the Highland Military academy.

*** Harold McCracken, Editor, Frederic Remington’s Own West, (New York, The Dial Press, 1960): 17.

**** Ibid.: 19. ‘Navvy’ was the term for laborer

February 21, 2013

By Richard J. Boyle, art historian and former museum director