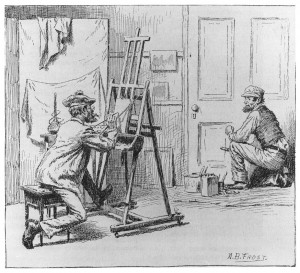

Arthur B. Frost (1851-1928)|Bonds of Sympathy, 1890|Cartoon for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine v. 81 # 482 (July 1890): 321|Pencil and ink on paper

Caption: Mr. Turps (who is doing a little job of painting in the studio). “Yes, sir: us painters has a many things to complain of. What with these ‘ere trusts raisin’ the price of ile

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907)|Portrait of William Merritt Chase, 1888|Bronze bas-relief|American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, gift of Mrs. William Merritt Chase

Arthur B. Frost’s cartoon, the Bonds of Sympathy is perhaps better known to us than most of Frost’s turn-of-the-century illustrations because Professor Sarah Burns used it as her first comparative image in her seminal treatise Inventing the American Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America. Dr. Burns’ interest in Frost’s contrast between a wall painter and an art painter rests in part on their respective head gear: the wall painter wears a billed cotton cap to protect his pate from paint spatters; the art painter wears a more fanciful tam-o’-shanter topped by a jaunty pom-pom. Burns explains that Frost’s art painter was based upon his friend William Merritt Chase’s habit “. . . of flaunting his artistic identity.” * Indeed, as Sarah Burns notes, the image is based on a bas-relief portrait of the painter by the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. An earlier study version of the cartoon attests, Frost was indeed seeking a caricatured image of the fine art artist that would be easily recognizable to the magazine’s audience.

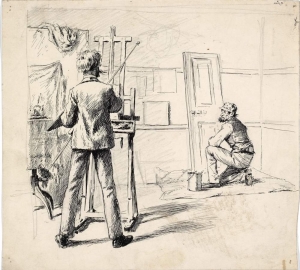

Arthur B. Frost (1851-1928)|Study for Bonds of Sympathy, 1890|Cartoon for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine v. 81 # 482 (July 1890): 321|Pencil and ink on paper|The Delaware Art Museum, DAM 2007-53

Compare the placement of artist and easel in both drawings. One stands, the other sits; one’s back is to the viewer so not much is seen of his painting activity, the other is viewed from the side so that we can see the canvas being worked on and the artist’s palette, handling of the paint brush, and the use of the maulstick on which the painting hand rests; while both figures sport exaggerated handlebar mustaches, only one wears a tam, the other is bare-headed. The still life set-up is more obvious in the finished work, while the study’s arrangement atop a cloth-covered pedestal is more elaborate. The artist in the study looks more like a gentleman, since it appears that he works wearing a suit since it is difficult to distinguish an artist’s smock in either drawing. And finally, the artisan-painter, as Burns describes him, in the study version works on a door removed from its hinges and in the finished illustration kneels in front of an oversized door in-situ with his brush obviously in hand.

What little training Arthur Frost had, was gleaned during evening drawing studies at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts under Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) beginning in 1882, when Frost was 31. Frost’s expertise was not merely drawing, but drawing with a comic bent. In an 1892 biographical article on Frost, Mr. H. C. Brunner described him as the first of the comic artists whose pictures “. . . are true to nature and funny at the same time.”**

So, if Frost’s penchant was to make comic images that tickled the American populace, why did he transform the easel-painter’s image for Bonds of Sympathy in the manner that he did? In the study Frost has not yet adopted the tam to help identify the fine art artist. It seems as though the easel-artist’s hair is covered with a wig in the study and that you can indeed see darker hair around his neck and ears. Beside the use of obvious artistic accoutrement identifying both of these characters as easel painters, what clues did Frost provide so that a viewer could see the obvious humor of this situation?

In the study drawing the exaggerated twirled handlebar mustache is the only part of the painter’s facial features we can see even while viewing him from the back. That same feature is craftily carried over in the finished illustration. In the United States, the handlebar moustache was considered stereotypically worn by characters of the wild west. In the art world too, outrageous moustaches were sometimes embraced by artists to create a flamboyant, memorable character. Other artists, or artist-types, used similar affectations in thier construced artistic roles.

For example, Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895), the society dressmaker nurtured his artistic role by adopting an artist’s wardrobe: the artist’s soft collar and floppy bow tie, a black beret, a fur-trimmed velvet cape, and a handlebar mustache. The famous architect Stanford White (1853-1906) trained his mustache into a flashy embellishment for his youthful face. An 1881-82 portrait of Chase reveals the painter as having an outstanding example of the exaggerated handlebar mustache. Chase was described as promoting himself “. . . as the genteel bohemian.”*** Since Chase and his elaborate studio were noted in the popular press, the cartoon of the fine art artist would be understood not only by the adoption of the tam-o’-shanter but also by the delineation of that elaborate mustache.

James Carroll Beckwith (1852-1917)|Portrait of William Merritt Chase, 1881-82|Indianapolis Museum of Art, Gift of the Artist, IMA10.8

*Sarah Burns, Inventing the American Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996): 21.

** H. C. Brunner, “A. B. Frost” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 85 (October 1892): 702. In the 1890s Frost resumed his studies, this time with William Merritt Chase in an attempt to loosen his painting technique and lighten up his hand.

*** Annette Blaugrund, The Tenth Street Studio Building: Artist-Entrepreneurs from the Hudson River School to the American Impressionists (Southampton, NY: The Parrish Art Museum, 1997): 105.

March 25, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator

Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Massachusetts