Anthropomorphism in Children’s Picture Books

By Jia Liu

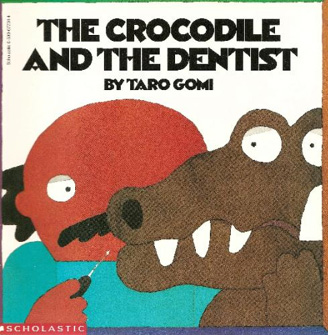

If we stop by the children’s picture book area in a book store, we find that more than half of the books are stories related to animals who are wearing human’s clothes, acting and talking like people; they are so normal to us, and children love them, rarely questioning why animals act like people. It seems to them that animals are supposed to have human personalities, just like children now born with tablet computer think the world originally had Ipads. Anthropomorphism, the attribution of human characteristics or behavior to animals or objects, is everywhere in our lives, especially in children’s picture books. Where did it come from?

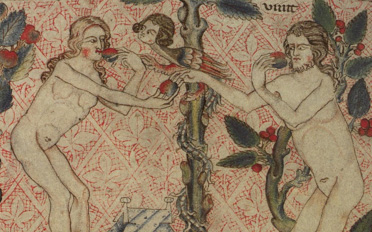

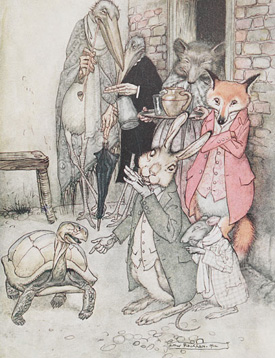

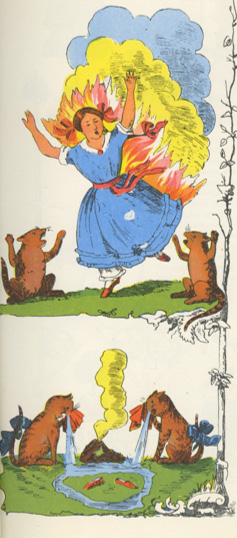

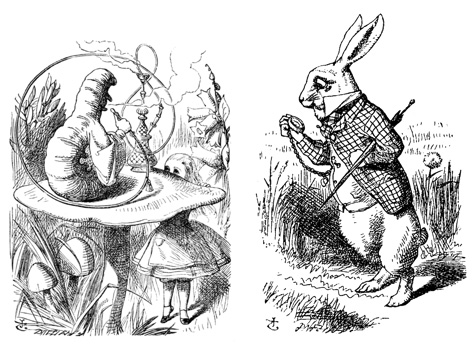

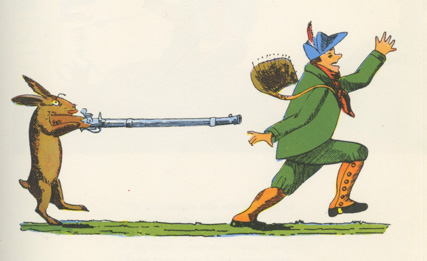

Anthropomorphism is a universal concept that appears in different culture, both western and eastern. It comes from human’s worship to nature and animals they live on. In Faces in the Clouds As a literary device, anthropomorphism can be found in a lot of ancient stories; some of them have written records and some of them are told orally. The most representative collection of anthropomorphic stories is Aesop’s Fables, compiled in 6th century BCE Greece, which includes The Fox and the Grapes,The Hare and the Tortoise,The Farmer and the Snake,and other stories many became familiar with as children. In China, there are also many anthropomorphic stories, but the most typical example is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, Journey to the West[2], a story about the legendary pilgrimage of a monk and his three protectors, a monkey, a pig and a demon. It was created in Ming Dynasty and the story was full of different animals, demons and gods. Just like Aesop’s Fables, the tales are popular with children but not created for children. Anthropomorphism was originally an instrument for adults, created for the purpose of instruction, preaching religion, or governing. Before the mid-eighteenth century, the notion of childhood, as we know it now, did not exist (Langrage Arts, Page 208)[3]; children were dressed in adult clothes and their playful curiosities often ignored. Children’s literature and illustration was virtually non-existent. It was John Locke, a philosopher, who first advocated targeting children as a special audience for the fables in Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693)[4]. He stated that “Aesop’s Fables are apt to delight and entertain a child… yet afford useful reflection to a grown man. And if his memory retains them all his life after, he will not repent to find them there, amongst his manly thoughts and serious business. If his Aesop has pictures in it, it will entertain him much better, and encourage him to read when it carries the increase of knowledge with it for such visible objects children hear talked of in vain, and without any satisfaction, whilst they have no ideas of them; those ideas being not to be had from sounds, but from the things themselves, or their pictures.” As the middle class developed and the emerging view declared that children are also self-aware, adults began catering to their emotional needs, and animals with human characteristics began to appear in children’s books. The following two versions of illustrations for The Hare and the Tortoise reflect how much peoples’ thoughts changed; the realistic hare and tortoise began wearing clothes and standing like people. Struwwelpeter (1845)[5] is considered to be the first children’s picture book that used anthropomorphism in illustrations. There are several stories which used talking animals directly, and the most well-known is The Dreadful Story of Harriet and the Matches. In the book, Harriet ignored the cats’ warning and played with; as a result, she caught on fire and burned herself to ashes, just leaving a pair of shoes behind. And when the good cats sat beside The smoking ashes, how they cried! “Me-ow, me-oo, me-ow, me-oo, What will Mamma and Nursey do?” Their tears ran down their cheeks so fast, They made a little pond at last. The illustration of crying cats is dramatic and filled with humor. Another story is The Story of the Wild Huntsman. In it, a hare steals a hunter’s musket and eyeglasses and begins to hunt the hunter. Looking at the complacent hare with his tongue sticking as the hunter runs away gives the reader a good laugh. The author, Heinrich Hoffmann, who illustrated the book as well, was a physician and director of a mental hospital. He believed it necessary to pay attention to children’s emotions and that children would find humor in the exaggeratedly gruesome consequences of misbehavior (Language Art, P208)[6]. Hoffmann created this book for his son as a Christmas present, and the little boy was delighted by the story and the lessons within. Struwwelpeter was created when most works for children were dry pedagogic books. Besides entertaining kids, education became the main purpose of children’s picture books. Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit was influenced by John Tenniel’s rabbit, and the visual connections are evident. The Tale of Peter Rabbit, published in 1902, had unprecedented success and became one of the most beloved children’s picture books in the world. Since it appeared 1902, and The Tale of Peter Rabbit has sold more than 40 million copies worldwide, and as of 2008, the Peter Rabbit series has sold more than 151 million copies in 35 languages. The popularity of Peter Rabbit shows an indisputable fact: children love animals with human characteristics. Why is anthropomorphism flourishing in children’s picture books? There is no doubt that children love animals. They often want pets because pets allow them to feel clever, protective and nurturing. Very young children don’t see animals as “other”, instead, they believe that animals have human characteristics. The appeal of animals as people can create a sense of emotional connection, making it easier to get involved in the story and remember it. Sometimes authors use animal characters because they can convey ideas by analogy, ideas which have greater impact than if child characters are used. For example The Crocodile and the Dentist, created by Taro Gomi, tells a story about a little crocodile who doesn’t want to see a dentist but has to go, and the dentist is really nervous about seeing his patient because he is a crocodile. The crocodile here is the key to the story. He has all the emotion a child would have when he goes to the dentist, which resonates with young readers. For adults, however, a crocodile is a dangerous animal, which is why the dentist is as nervous as his patient. Finally, the crocodile goes through the horrible treatment, and all the tension turns into relief and laughter. The anthropomorphic format reassures children through humor, which might not have been possible if Taro Gomi used a child character. Notions of education through children’s literature has developed through the years, and anthropomorphism continues to evolve as a significant tool for engaging young audiences. In Struwwelpeter, the purpose of the story is to teach important lessons in a humorous way, such as not to play with matches or do things without adult permission. The lively animals soften the didactic tone and ease the tensions raised by dealing with problems. Today, children’s picture book entertain and inspire children, with more focus on developing their imagination and creativity. Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus is about a pigeon who come up with lots ideas to persuade a grownup to let him drive the bus. Just seeing the pigeon talking and imagining how he might drive the bus as he pleads, wheedles, and begs his way through the book, invites children to participate in and decide his fate. This simplified pigeon occupies the whole book but creates space for kids to imagine. Sometimes instead of educating kids, children’s picture books also try to address and illuminate the world of adults. Anthony Browne’s Zoo depicts an interesting trip to the zoo. The story portrays a rude, thoughtless father and an indifferent adult world, encouraging adults who read to their children to consider their actions and the environment they are creating for the youngsters in their care. In the book, the illustrator gives humans animal characteristic to satirize their situation and actions, another approach to the use of anthropomorphism. Anthropomorphism has a deep roots in children’s literature and visual storytelling and continues to have great value in illustrated picture books across generations today. [1] Stewart Elliott Guthrie, Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion .New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. [2] Wu Cheng’en, Journey to the West, c. 1592(print). [3] Bruke, Carolyn L.; Copenhaver, Joby G. Animals as People in Children’s Literature, Language Arts, v81 n3 p208 Jan 2004. [4] Locke, John, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, London, 1693. [5] Hoffmann, Heinrich. Struwwelpeter, London, 1845. [6] Bruke, Carolyn L.; Copenhaver, Joby G. Animals as People in Children’s Literature, Language Arts, v81 n3 p208 Jan 2004.  After the mid-eighteenth century, more and more anthropomorphic illustrations appeared in children’s book and they were quickly developed. A favorite illustrator of this period is John Tenniel, who was well known for his vivid illustration of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). We observe the caterpillar whose legs turn into man’s arm, , and the rabbit wearing a plaid coat, looks much more man-like than Heinrich Hoffman’s revenge rabbit.

After the mid-eighteenth century, more and more anthropomorphic illustrations appeared in children’s book and they were quickly developed. A favorite illustrator of this period is John Tenniel, who was well known for his vivid illustration of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). We observe the caterpillar whose legs turn into man’s arm, , and the rabbit wearing a plaid coat, looks much more man-like than Heinrich Hoffman’s revenge rabbit.