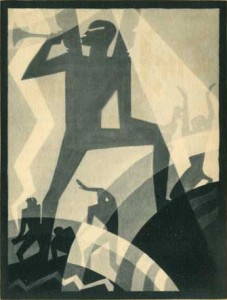

Aaron Douglas (1899-1979)|The Judgment Day|Illustration for God’s Trombones, by James Weldon Johnson (New York: Viking Press, 1927)|Medium unknown|Location unknown

Standing with one foot on a mountain and one in the middle of the sea, the angel Gabriel sounds his silver trumpet, signaling the end of the world. Mankind’s saved raise their hands to be received into heaven while sinners are thrown into the fiery mouth of hell. This illustration was created by Aaron Douglas to illuminate one of poet, writer, musician, politician, educator and political activist James Weldon Johnson’s (1871-1938) seven traditional African American sermons presented in free-verse poetry in God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, published in 1927. Johnson wrote God’s Trombones in an attempt to pay tribute to the black preachers and their classic sermons he remembered from his childhood. The book was published during the flowering of African American intellectual life in the 1920s and 30s, known as the Harlem Renaissance. It was a time of intense focus by the African-American creative community to produce creative materials which preserved and chronicled black history and folk culture. The following is an excerpt from “The Judgment Day,” the last poem in the book for which the above illustration was made:

Oh-o-oh, sinner,

Where will you stand,

In that great day when God’s a-going to rain down fire?

Oh, you gambling man — where will you stand?

You whore-mongering man — where will you stand?

Liars and backsliders — where will you stand,

In that great day when God’s a-going to rain down fire?

Aaron Douglas’ rise from Midwest high school art teacher to illustrator laureate of the Harlem Renaissance was nothing short of meteoric. In 1925, Douglas had, somewhat reluctantly, left his teaching position at Lincoln High School in Kansas City and moved to Harlem at the behest of Charles Johnson, the publisher of Opportunity magazine. Douglas began his New York adventure sleeping on the couch of Johnson’s secretary while taking painting lessons from Winold Reiss (1886-1953). His first illustration assignments were creating covers for Johnson’s Opportunity magazine and for The Crisis, W.E.B. Dubois’ periodical for the NAACP. Douglas quickly found a place in the inner circle of the creative life of Harlem.

The year 1927 witnessed an unprecedented outpouring of seminal literary works by Harlem Renaissance writers, and Douglas was seen by the African American community as the illustrator of choice. In a single year, he was commissioned to illustrate Countee Cullen’s Caroling Dusk, Langston Hughes’ Fine Clothing to the Jew, Charles S. Johnson’s Ebony and Topaz, and Gregory Montgomery’s Plays of Negro Life in addition to Johnson’s God’s Trombones.

It is interesting to note the influences that inform Douglas’ quickly maturing illustration style during this period. While the illustrators of America’s mainstream periodicals were emulating a classic, literal style, Douglas was clearly taking his cues from the European avant-garde. His highly stylized, allegorical imagery and geometric draftsmanship bear a resemblance to the work of European art deco poster designers such as A. M. Cassandre (1901-1968) (who was also an influence evident in the work of his German-born teacher, Winold Reiss). Douglas’ use of nonrepresentational line to separate fields of color resembles a similar technique used in the cubist works of Picasso and Braque.

Douglas’ sparing use of color was as much a pragmatic choice as an aesthetic one. The publications for which he was illustrating in his early years were modest-budget journals, and, at the time, four-color process was a relatively new and expensive technology. Douglas’ use of hard lines, flat values and grisaille execution ensured that his work would reproduce well in publications of a limited budget.

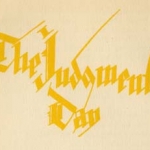

In addition to the eight illustrations Douglas provided for Johnson’s book, he created calligraphic titles for each of the poems. His lettering style, printed in yellow-gold in the first edition, is a loose, free-form variation of classic Old English, which, in its unaltered form, it is the typeface that would be the obvious choice for a Biblical or religious text. Douglas’ spin on the letterforms creates a feeling that is at once ominous and whimsical; as if he is simultaneously regarding the mythic figure of the traveling Black preacher with reverence and caricaturizing his histrionic tone.

February 18, 2010

By James Gilbert, Curatorial Staff

Norman Rockwell Museum