A Rosie is a Rosie is a Rosie

by Shreyas Krishnan

Rosie the Riveter was Norman Rockwell’s cover for the May 29, 1943 issue of Saturday Evening Post. We see an androgynous figure seated with the kind of practiced confidence that not many are capable of, even as her skin shines with grease and she sits in sensible, over-sized (yet cinched at the waist) overalls. She balances a heavy riveting machine with nonchalance, while eating a sandwich. Her lunchbox tells us that her name is Rosie. Her feet rest firmly on a yellowed copy of Mein Kampf, and her open visor mimics an angel’s halo. With the looming stars and stripes in the background, and her clothes which echo the colours of the flag, the mise en scene of this painting impresses upon even the most clueless of viewers, that this woman is of great importance to the American identity during World War II.

But who was Rosie? Her first appearance seems to be in Rosie the Riveter, a 1943 song written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb about a woman factory worker. “She’s part of the assembly, She’s making history, Working for victory, Rosie, the Riveter.” Rosie, like her predecessor Ronnie the Bren Gun Girl – a real Canadian icon Veronica Forster, featured on Canadian promotional material from World War II – was one among many redefining portrayals of American women in popular graphic art during the War.

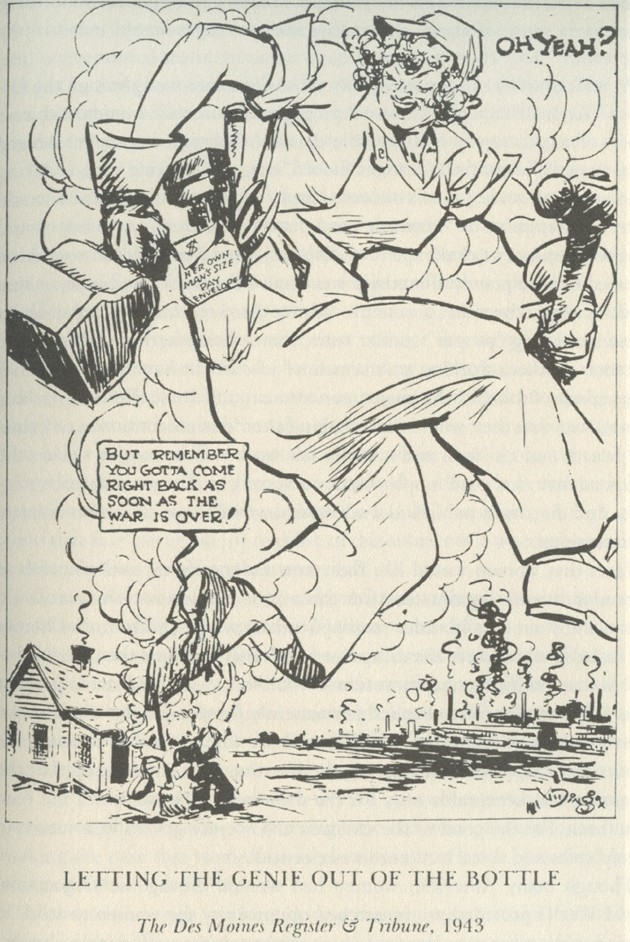

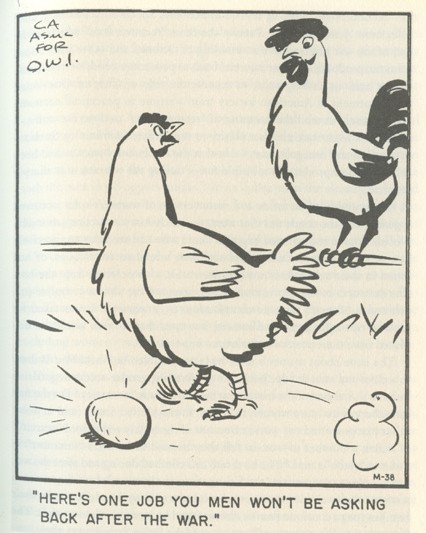

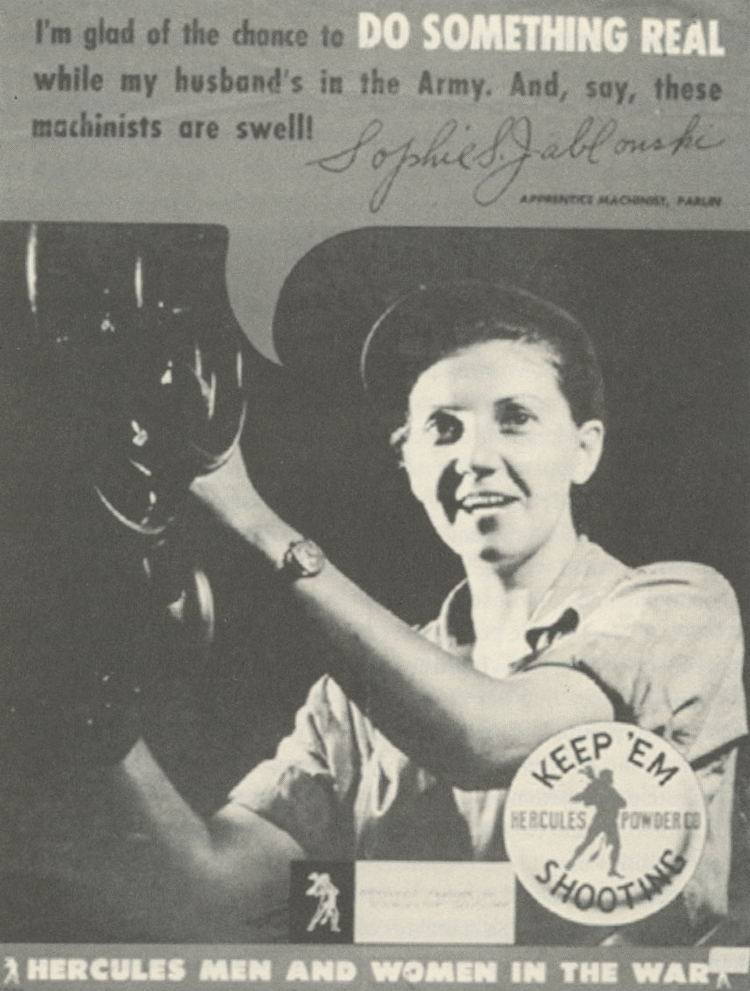

During and after the war, the US Government and its Office of War Information (OWI) commissioned a vast body of illustrated material created to eliciting very specific contributions from the public, from attracting people to enlist to fight the war, to extolling its women to leave their traditional role of homemakers and occupy the factory positions that were left empty when men were deployed to fight. The latter goal was achieved through a carefully curated identity that Rosie has now come to epitomize.

In her first visual form on J Howard Miller’s We Can Do It poster for Westinghouse, a yet unnamed Rosie was simply a face, like the other women in war-time promotions; her appearance, attire and gesture were perhaps based off real life. Although Miller’s poster came first, Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post cover solidified the concept, or the idea of this character.

We are constantly dictated by popular (and usually, male) notions of the female ideal. In the essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Laura Mulvey talks about scopophilia (pleasure in looking), specifically in its narcissistic aspect. The desire to look conflates with the desire to be. The screen – in this case, the image – becomes a mirror, that viewers hold themselves up to. The need of the hour in 1943, was women who would be willing to take on roles that they had been conditioned to believe they were incapable of performing, roles that were traditionally considered masculine. The most effective way to do this was to create a new kind of aspiration. The posters directed at women by the OWI worked towards creating a notion of masculinity for women, one that could co- exist with their femininity; a non-threatening hybrid that would enable women to remain feminised enough to remain conventionally attractive and masculine enough to be efficient (Knaff, 69).

Next to Wonder Woman (the first female comic book superhero who made her first appearance in 1941), Rosie and her many avatars became the ultimate (accepted) straddlers of gender identity in the 40’s – perhaps the changing of ‘Ronnie’ to ‘Rosie’ allows more room for this straddling. When seen in context of other prevalent Rosies of the time, like J Howard Miller’s, Rockwell pushes the portrayal of gender in his painting of Rosie, offering a more interesting insight into how easily gender as a notion can be created. Rosie’s masculine affect here has often been attributed to the lingering memory of Michelangelo’s painting of the Prophet Isaiah.

Both Rosie and Isaiah are seated in the exact same manner, their left hands held up, and their heads turned away from the audience. But the masculinity that Rosie wears here goes beyond simple mirroring. As Judith Halberstam says in her book Female Masculinity, masculinity becomes legible as masculinity where and when it leaves the white male middle-class body.

Unlike his contemporaries, and even artists after him, Rockwell did not paint women as simply objects, instead portraying them with a more everyday and ‘real’ beauty, and in a sense redefining the tropes of beauty existing at the time. In his autobiography he wrote, “Every artist has his own peculiar way of looking at life. It determines his treatment of his subject matter. Coles Phillips… and I used to use the same girl as a model. She was attractive, almost beautiful. But in his paintings, Coles Phillips made her sexy, sophisticated, and wickedly beautiful. When I painted her she became a nice sensible girl, wholesome and rather drab”.

The effect of gender is produced through the stylization of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements and styles of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self. Rosie’s femininity and masculinity are both not just created, they have been carefully curated, just as an actor would wear costumes and personality keeping with the character being enacted. In fact, the model for Rockwell’s painting was a nineteen year old, 110 pound phone operator, Mary Doyle Keef

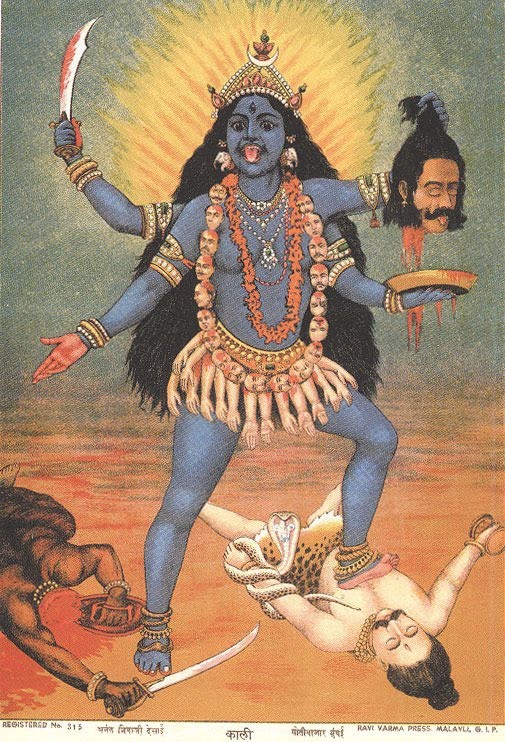

This visual of Kali was by the Indian artist Ravi Varma who, interestingly, was a pioneer in using the European realistic painting style to depict scenes from daily life and Hindu mythology. He was also the first to create lithographs of his work, proliferating his visuals of gods, goddesses and mythological scenes to an extent that they very quickly and enduringly shaped and became a part of public memory).

Each new drawing we do contains the memory of our past drawings (Heller and Arisman). And often that unconscious personal memory plays on a larger unconscious collective memory. This sort of intertextuality allows us to connect and relate images and texts to each other through time. More distant parallels can be drawn with Indian art. In Hindu mythology, the goddess Kali was

created to vanquish demons that the gods could not fight because they were the granters of boons that protected the demons. Kali, the embodiment of power, was stronger than all the male gods. Kali is traditionally shown in blue, clothed only in the spoils of her victories, holding her weapons in her many hands, with her foot pressing down on a demon or a vanquished force. Her violence is her masculinity. But as powerful as Kali is, she can also be a maternal figure. The depictions of Kali and Rosie overlap with Wonder Woman, whose display of masculinity was threatening only to the villains in her stories. (Knaff, 123).

The key, to Judith Butler’s idea of gender performativity, is repetition. As in other ritual social dramas, the action of gender requires a performance that is repeated. This repetition is at once a reenactment and reexperiencing of a set of meanings already socially established. (Cleto, 366). In the case of Rosie, Kali, Wonder Woman and all of the other portrayals of women in the war-poster canon, their performance of gender is reenacted and reexperienced through a literal and mass repetition – print reproduction and proliferation in the form of posters, magazines, lithographs, comics.

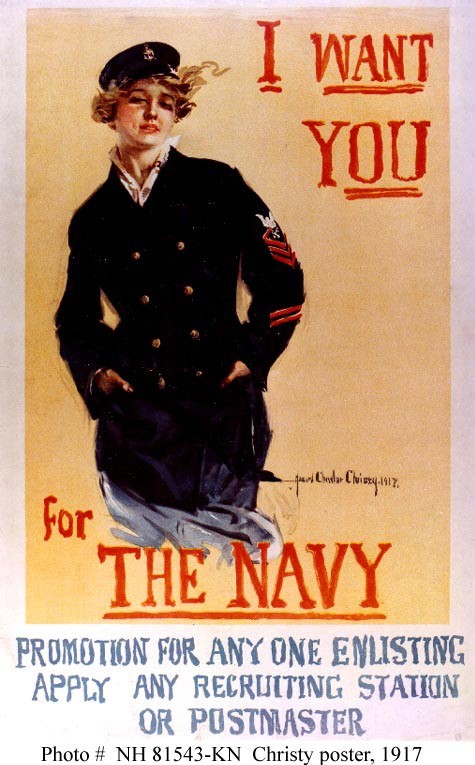

Under similar, yet different, circumstances during World War I, Howard Chandler Christy’s recruitment posters for the US Navy in 1917 shows us the ideal woman of that wartime. Delicate, pretty, seductive. They are hyper- feminised, akin to ordinary women wearing an exaggerated womanhood. Gender roles are clearly defined here – these girls are present solely to sell the poster. They are not men, and therefore cannot do much else. Here, again, it is clear that gender differences can be created, erased, or reversed, depending on the context. (Hyde 2005, 589 / qtd in, Connell 65) At the end of the war, soldiers returned and the Rosies who had been so carefully persuaded out of their homes, found themselves being pushed back in there. In parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan, there is a cultural tradition known as Bacha.

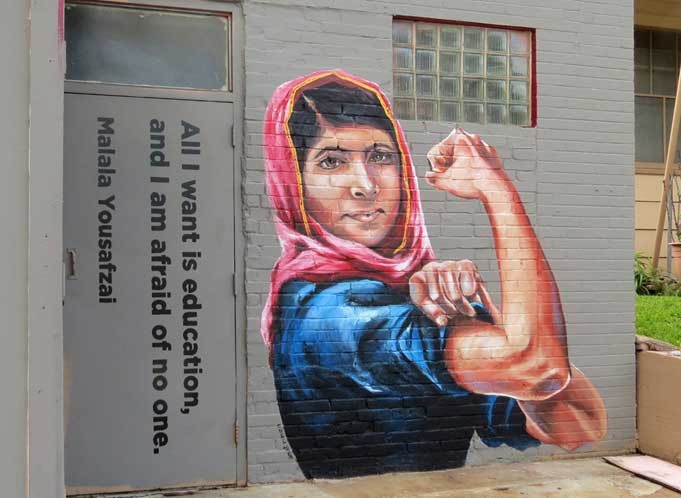

Posh, where in the absence of a male family member, a family and community is allowed to nominate and treat a girl child as a boy – the Bacha Posh. The child is dressed, addressed and given the duties and privileges of a young male, even though she is known to be a girl, but only until she reaches puberty. After that the bacha posh must discard her temporary masculinity and return to womanhood. At the time of its creation, Rockwell’s Rosie overshadowed all her other instances, including J Howard Miller’s We Can Do It poster. Interestingly though, the explosive popularity of Miller’s Rosie in today’s world belies the original brevity of its first appearance. Perhaps its non-specific content, as compared to Rockwell’s obvious patriotic references, lends naturally towards the phenomenon of Rosie re-appropriation. From her origins as an unnamed woman, the present- day Rosie is an idea that transcends her history in the canon of war-time imagery, into a new canon of female empowerment.

Rosie is a call to action, a representation of achievement in the face of odds, a new aspiration. The newer and repeatedly re-appropriated storytelling that revolves around Rosie has become so entrenched in our shared memories, that the original character or the actor herself is no longer required to communicate her presence. Even the gesture that she is so well known by can be done without. Simply her costume or her drag–the red headscarf and a blue outfit–will suffice.

Works Cited

https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2013/07/01/art-entertainment/norman-rockwell- art-entertainment/rosie-the-riveter.html

Palmore, Haley. https://www.nrm.org/2014/02/beyond-objectification-norman-rockwells-depictions-of- women-for-the-saturday-evening-post/

Rockwell, Norman. My Adventures as an Illustrator

Heller, Steven and Arisman, Marshall. The Education of an Illustrator

Connell, Raewyn Gender

Cleto, Fabio Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject – A Reader

Knaff, Donna. Beyond Rosie the Riveter: Women of World War II in American Popular

Graphic Art, 2012

Gluck, Sherna. Rosie the Riveter Revisited: Women, the War and Social Change, 1987

About Shreyas R. Krishnan

Shreyas Krishnan is an illustrator-designer with an eye for the everyday and an affinity for the drawn image. She is currently engaged in the MFA Illustration Practice program at Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore. She loves print, mythology, multiple narratives and obsessively documents life around her in her many visual journals. Shreyas is passionate about women’s studies and issues and is greatly interested in people, their stories and cultures, and the idea of nationality.